Playgirl folded in 2008 — and in the years since then, a handful of blogs have taken up the mantle of shamelessly objectifying men. There’s Jezebel’s Thighlights, the work of BuzzFeed writers like Katie Heaney and Matt Bellassai, and the Cut’s own Dong Watch and Male Gaze. But does doing this make us hypocrites? By objectifying men, do we undermine our criticism of those who would objectify us?

No.

Yesterday, Daily Beast writer Emily Shire argued that Jezebel’s nude rendering of Disney princes “perpetuates the same pressure on men to exhibit a certain physique that [Jezebel] critiqued Disney of doing to women.” That may be. But Shire has missed what makes exerting that pressure so fun. “Not being objectified” is just one of the many advantages of being male. When we selectively revoke this freedom from body scrutiny, we don’t do anything to diminish the meaningful economic and reproductive advantages men enjoy.

Put another way: We will stop Dong Watch once there’s a female president, zero wage gap, and Swedish-level paid parental leave; once tampons, birth control, and abortions are all available free and on-demand.

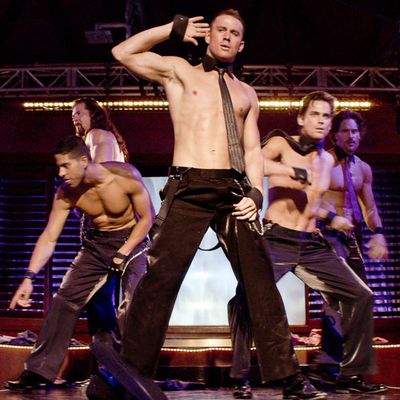

Here’s a handful of recently objectified men, and why I think they’ll be okay.

Jon Hamm: No critically acclaimed human G.I. Joe ever lost a role because his dick was too big. Unlike a face that’s too pretty or a body that’s too large, you can just put a dick away.

World Cup Soccer Players: Slate’s Amanda Hess explained this one best. Unlike their underwatched, underpaid female counterparts, male professional athletes don’t need to be conventionally good-looking in order to get media coverage and corporate endorsements. “When it comes to coverage of male soccer, sexual objectification is the icing, not the cake,” she wrote.

Justin Theroux: The son of a journalist and a corporate lawyer, Theroux is white, male, privately educated, and handsomely compensated. Through marriage, he will reportedly combine his fortunes with Jennifer Aniston, who is worth $150 million.

Gaston, Prince Eric, and Aladdin: They’re made-up animated characters.

Of course, most people don’t object to objectification because they’re worried about the objectified party. (In fact, because beauty is a privilege, we must hear arguments that objectification is a compliment.) Shire’s concern is instead for the self-image of the girls and boys who internalize Disney body standards: waists so small that the princesses would snap, shoulders so large the princes would topple. “That physical insecurity can apply especially when it comes to the part of the male anatomy so glorified and critiqued in ‘Disney Dudes’ Dicks,’” Shire wrote. But again, this argument ignores the power imbalance that gives the joke its context. Disney is a corporation that makes children’s movies whose characters — licensed for dolls and fruit snacks and lunch boxes — are more or less unavoidable. Jezebel is a site for grown-ups known for its frequent satire of such media. Disney is still the dominant force here, dick drawing or no dick drawing.

I could tell you that the Dong Watch is our attempt to show men how it feels to be objectified, either to make them sympathetic to our cause or out of pure retribution. But either would be false. Male objectification isn’t about making men feel bad. It’s about not caring how men feel. Or at least, putting it aside long enough to think about what we desire. As long as the covers of men’s and women’s magazines are both devoted to what men want, that will feel pretty cathartic.