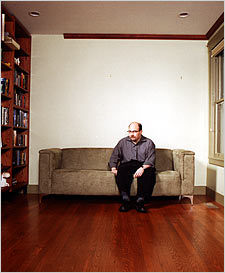

The Exploder of Journalism and I have an appointment at noon at a café near the Haight in San Francisco, and he’s right on time in the Kangol hat. To be honest, he’s not much to look at: short and balding, with a little smile and round cheeks with bright-pink patches of color. Modish glasses. Weighing in at 210 in briefs (yes, I asked). He says hello to Nico (the dog) and Steve and Misha behind the counter, then I follow him to the back terrace, where the Exploder gets down on all fours to give Bob, a white cat, some fish treats from his pack.

He wipes his hands on his black jeans. “Cat saliva. Maybe that’s why I’m allergic.”

His phone rings. It quickly becomes clear that he’s talking to law enforcement, and they’re trying to nail a child-prostitution case. The Exploder, who believes in good citizenship, is telling a prosecutor how to subpoena Internet-service providers’ info on bad guys, and how much he wishes they had artificial intelligence to help out. He pauses and rolls his head back, a sure sign that a joke is coming.

“Unfortunately, our artificial intelligence is not that good, and when it is, it will kill us and take over, and then we’ll have to send someone back in time to kill us, and Arnold Schwarzenegger isn’t good at that anymore … ”

Ha-ha. The Exploder of Journalism has a hokey sense of humor forged by Oedipal issues; the life sentence inside the short, round body; and seventeen years at IBM, where managers crapped on him and did not recognize that underneath that pink-cheeked, abrasive demeanor was an action figure called the Exploder of Journalism.

“Let’s go now. My bladder is full—”

He has to stop in at Radio Shack, then get to his job in customer service (don’t all geeks who took the buyout from IBM?). I want to hail a cab, but this goes against his code, so we wait for the 43 bus. Being short makes it easier for the Exploder to deal with the bus’s lurching and swaying on the hills of San Francisco. He sets his feet apart and his briefcase on the floor and surfs the bus like the nebbish superhero he is.

When we get off, he leans in close. I brace myself for the warm breath of a personal confidence.

“That’s good till 2:30.” He touches my transfer slip. “They won’t check you on the trains; they might on the buses.” Roger.

Up some stairs to his office. A huge guy at a computer that looks like a modular couch and appears to be running a nuke plant swings around in his chair. He’s got a plate in one earlobe, almost a dish. I’m afraid to see what else. “Hi, Craig,” he says sweetly. All right, yes—it is. It is Craig.

In the past few months, I and countless others in the mainstream media have awakened to the fact that something we thought was benign and even modestly beneficial, if we happened to have a room to rent or something to sell, was in fact a wild beast, loose in the orchards. Craigslist.org is changing everything. A simple and free online classified-ad service started by the gnomish Craig Newmark in San Francisco eleven years ago, Craigslist is (a) where young urban people conduct much of the traffic of their lives, including renting apartments, finding lost pets, and getting laid in the middle of the day, and is (b) thereby destroying classified revenues for big-city newspapers, which are already in crisis, and so it has become (c) the symbol of the transformation of the information industry. Rocked in a Bay Area cradle of left-wing values, Craigslist has built a huge national community by word of mouth. The site is free and without advertising (with the exception of help-wanted ads in three markets), and it gets more than 3 billion page views per month (10 million actual users a month), ranking it seventh on the Net, not so far behind Google and eBay.

Craigslist’s largest category is New York apartments, where it posts more than half a million listings a month. Yes, half a million (many of these repeats).

The soul of the site is expressed by the simple populist formulation that Craig Newmark states over and over again when he is asked about his purpose: “We are just trying to give people a break.” Users throng the site not only because it is free, fast, and stripped-down but because of the communitarian values flowing from the founder. In refusing to take the business public or to sell any display advertising, Newmark has “stepped away from many millions,” he says. Maybe billions. His users all know that. The site’s only income is the $75 per listing for job posters in San Francisco, and $25 per listing in New York and Washington, D.C., earning a sum estimated by Fortune to be $20 million a year.

Civil meltdowns like 9/11 and Katrina have only built that community. During the transit strike, Scott Anderson, a blogger for the Tribune Company, noticed with sadness that the ride-share space on Newsday.com, a Tribune holding, was empty while Craigslist was going crazy with offers. “Yet another crisis and Craigslist commands the community,” he wrote. “How come Craig organically can touch lives on so many personal levels—and Craig’s users can touch each other’s lives on so many levels? It’s just frustrating that even when we [newspapers] try, we more often than not find we are absolutely losing what may be one of the most important parts of the business as it more and more moves online—the ability to connect people to one another and to activate conversations. To not just be the deliverer of news and information … but the catalyst of connection.”

Craig is not content to merely eat away at the business model of newspapers by chewing up their classifieds, from back to front. He’s also begun issuing vague pronouncements about citizen journalism, the people—his people—taking the news into their own hands. “I’m working with some folks on technologies that promise to help people find the most trusted versions of the more important stories,” Craig said on his blog, further spooking the old-media types. Newmark has invested in a Website headed by Jeff Jarvis, a longtime journalist and blogger—“to organize the world’s news using the best of technology, community, and editors,” he wrote on his blog. Jarvis says the site will be up in the spring and aims to help newspapers redefine themselves at a time when the journalism world is shattering.

At media conferences, Newmark introduces himself by saying that he does customer service at Craigslist, and gets a laugh. But then he is seated beside Arthur Sulzberger Jr. (“I’ve … enjoyed his company,” the publisher told me in an e-mail) and is photographed making jokes with Martha Stewart. During one of my meetings with him, Newmark broke off to take a call from a business magazine that apparently wanted to picture him destroying a newspaper.

“That would be hurtful to people. I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to do anything undignified.”

This month, Newmark will be in New York to take part in a real-estate conference at which he will talk about a proposed $10 fee per ad to try to tame the traffic on the apartments site (the volume is actually a problem for him, because many of the ads are either repeats or scams), even as a new film called 24 Hours on Craigslist opens this month at the Pioneer in the East Village. He will also drop in on some real-estate brokers’ offices.

“The usual response is panic, followed by photography,” he says. “Somebody whips out a camera. Often several cameras.”

“You’re a celebrity,” I say.

“Not a celebrity. I’m a guy who may or may not exist. I want to assure all your readers that I don’t exist. I’ll add, as a bonus joke for all the physics nerds, I exist in a state of quantum superposition, simultaneously existing and nonexisting.”

The celebrity is a by-product of the large social powers that Newmark and his even more idealistic CEO, Jim Buckmaster, have unleashed for the list’s true adherents, struggling urbanites. “My whole life is based around it,” says Rachel Beider, a 22-year-old photographer on the Lower East Side. “It’s my only source. I use Craigslist for my apartment, for finding roommates, to get my cat, come to think of it—for everything.” Her statements are seconded by a 59-year-old artist on the Upper East Side who has gotten roommates, sold furniture, joined a singing group, and hired a computer repairman “for $5 and a Coke” through the list. “I feel like it’s revolutionary what Craig is doing,” she says. “I have isolationist tendencies, and for someone like myself, this has been a huge miracle.”

The only thread in Newmark’s autobiography is social isolation. “I was academically smart, emotionally stupid,” he says. “I can’t read people, and I take them too literally.”

Although Craigslist does no marketing surveys, the “power user” of the site is someone who’s not settled, who’s looking to fill basic needs. And this intense use of the site gives it its small-town feeling.

In December, a Boston woman who had left her iPod on the Orange Line promptly posted on Craigslist and soon got the player back, after describing her playlist to the man who had found it. About the same time, a woman in South San Francisco lost her dog and posted repeatedly on the list before she got a call from a worker at the Moss Rubber Company. “Even though my dog had a microchip, the real savior was posting to Craigslist,” the dog owner wrote, “where everyone goes when looking for something.” Rachel Beider misplaced her destiny. A few months back, she exchanged eye contact with a tall blond guy on the train, then got off before either of them could say a word. She went home and posted “To the cute blond guy on the L Train” in the Missed Connections category. Within hours, Daniel Atwood had e-mailed her to ask, “What were you listening to?” “Azure Ray.” This month, she and Atwood are going to India and Southeast Asia together for several months. “Do you know how hard it is to meet vegetarian guys?”

Among media mandarins, the list began to resonate a year ago, after a business study in the Bay Area showed that local newspapers were losing as much as $50 million a year in revenue to Craigslist. The awareness of the trend has since avalanched. Classifieds make up as much as 50 percent of big-city newspaper ad revenues, explains newspaper analyst John Morton, and at a time when the newspaper industry is in crisis, with circulations going down by as much as 2.6 percent a year as readers die off and the young go elsewhere for their information, Craigslist has gotten a reputation as the newspaper killer.

At the convention of the American Society of Newspaper Editors last spring, two panelists at a session on the crisis in the industry flashed a slide of Newmark and asked the editors how many of them knew who Craig Newmark was. A faint show of hands. Craigslist? A few more.

“The shocking thing is that this was someone who was not only a threat to steal their business but was in the process of doing it,” says Jay Rosen, a blogger (the name of his blog is PressThink) and professor of journalism at NYU. “What industry could survive in which you don’t know the name of the person who is taking away your business? They’re mystified. They don’t know who this guy is and where he came from. And it just shows—that it’s easier for Craig to learn journalism than it is for these guys to learn the Web.”

From a business standpoint, this may be the most revolutionary aspect of the Craigslist model: It took what had long been defined as a profitable industry—classifieds—and demonstrated that it is not much of a business at all, but is rather what open-source advocates call “a commons,” a public service where people can find one another with minimal intervention from their minders. Even so, the revenues from the tiny portion of ads Craigslist charges for are so considerable that Microsoft and Google and eBay have all come up with competitors or have announced plans to do so.

Newsmen have not observed the rise of Craigslist without comment. The SF Weekly (itself once the venue for hip classifieds) lately attacked the site as “craig$list.” And Al Saracevic, a business columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, issued a challenge to Newmark: “You shouldn’t take the money and run … [You] need to give something back to society other than cheap apartment ads and funny, dirty personals.”

And even though the amount of money Newmark is taking from the list is modest, Newmark said, “Al’s right.”

That was last spring. Chronicle editor Phil Bronstein says he is still waiting for an answer from Newmark. It’s hard to escape the sense that the architects of the new media are less likely to be Bronstein’s (and my) crowd of ink-spotted kids who grew up reading the Pentagon Papers and All the President’s Men than they are to be tech nerds like the Craigslist people.

“Jim and Craig are engineers,” says Bronstein. “I’m an editor. I’m paid to make choices. My work still has meaning—but does it have value?”

It is a paradox (but a logical one when you consider it) that a great social innovation came out of a great social disability. Craig Newmark is one of the most socially impaired people to be found this side of a high-school reunion. Yet he is also an extrovert who thrives on seeing and talking to others. And this large need, hooked onto his extreme deficit, is really the only reason that Craigslist is now in 190 cities around the world.

Craig was born in December 1952, the first son of a salesman (of insurance and meat, among other things) and a bookkeeper mother who had met three years before at a synagogue dance. The setting was Morristown, New Jersey, but Newmark likes to say that he grew up in “Nerdistan.” Science fiction was his literature, and by 13 he had formed his lifelong ambition: Master quantum physics.

“That supplanted dinosaurs.”

The two large psychological facts of the Newmark family seem not to have registered at all. His father, Leon Newmark, died of cancer shortly after the boy’s bar mitzvah. What effect did this have? “I think probably nothing. I may be very wrong. I don’t know of any effect.”

And what about Joyce Newmark’s struggle to raise two boys—did that shape the man whose only principle of action for the past ten years has been to give other people a break?

“I don’t know. I know single moms don’t get a break, which is part of the motivation for our child-care category. But I don’t know if it relates to my own childhood. Our memories are treacherous, and we suppress things. I had some developmental issues. Being a nerd, I had some problems getting along with other kids.”

The only thread in Newmark’s autobiography is social isolation. “I was academically smart, emotionally stupid. I can’t read people, and I take them too literally,” he confesses. In classrooms, he says, he experienced “tiny amounts of anti-Semitism,” but quickly amends that. “Frankly, any problems related to prejudice I faced may be because I was a show-off about academic stuff, raising my hand and answering questions. Or because I’m short. Five seven.”

In high school, he fell in love with the computer, and when he got to Case Western Reserve in Cleveland, he designed his own curriculum in computer science. It was also at Case Western that in his sophomore year he had an epiphany. Looking around the room in a communications class, he realized that not everyone had a communications problem, only he did. “It had to be me. I had difficulty communicating with most people.”

Cut to Detroit, and Boca Raton, and seventeen years in the IBM hinterlands as a systems engineer. Newmark was “mistreated by managers,” says Anthony Batt, a friend. Newmark demurs. “Some of them were trying to help me, and I didn’t get it. Occasionally, I was probably a bit of an asshole. I had difficulties dealing with people.”

Everything changed in 1993. He moved to San Francisco to work for Schwab, and the city’s spirit of personal experimentation and techie progressivism made him feel home at last. He joined the Well, the pilgrim colony of idealists on the Web that struggled with issues of free speech and intellectual property, led by Stewart Brand, whose koan was “Information wants to be free.” He was part of the Linux-inspired open-source movement, which looked on Microsoft as so much vinyl-siding tract housing on the Net’s sweeping landscape. And he entertained himself at events like the Anon Salon and Joe’s Digital Diner.

“I learned that storytelling is important,” he says.

Newmark is more practical than egghead, but the Well’s discussions of Internet community engaged him at his core. He saw people giving hours of time to one another without compensation, including professionals helping people in emergencies; he wanted to take part. So in 1995, he began sending out a list of techie events and opportunities to friends. Internet jobs, apartments, lectures. Just ten or twelve people at first. But the list grew. Within a few months, his list cracked the e-mail ceiling on CCs, 240, and so had to move to a listserv, and he had to give it a name.

A word about Newmark’s friends. He lacks interpersonal skills; he doesn’t connect. “He’s much more comfortable in e-mail than in person-to-person contact,” says programmer Weezy Muth. It struck me that he can barely distinguish between one human integer and another. On the evening following our first meeting, of four hours, Newmark failed to recognize me when I came up and introduced myself at a lecture to which he had directed me. “Bill, did you say?” Then in the hall, he threw himself down two seats away from me. He compensates for his clumsiness with the trick of trying to memorize first names. But these spray out like robotic data points, and the one-size-fits-all party talk that ensues paralyzes all within earshot.

But back to the hero ballad. Newmark wanted to call the listserv SF-events. “To hell with that, don’t make it fancy, just keep it Craigslist,” Batt said—it’s what everyone calls it anyway.

The list passed a million page views a month, and Newmark was using PERL-based code that converted e-mails to Web pages so that he could instantly publish friends’ ads. Microsoft Sidewalks (a now-defunct city-by-city Web network) approached him about running ads on the site. He said no. But he incorporated as a for-profit in 1999, quit his day job, and gave away a 25 percent share of ownership to a staffer, Phillip Knowlton, in the belief that Craigslist was a community trust that belonged to everyone. Besides, he says, he thought that if he owned the whole thing, he might develop a fat head and get “middle-aged crazy.”

Like its founder, the site had a straight and unpretentious look, without graphics, like an early Internet application. This may be Newmark’s genius. He expresses himself with a simple, naïve-sounding fervor: “The purpose of the Internet is to connect people to make our lives better.”

In 1999 the dot-bomb hit, and in 2000, amid the wreckage, Newmark made his most important hire, Jim Buckmaster, a shy, black-haired programmer fully a foot taller than Newmark who had been working at a dead start-up called Creditland.

Raised a Methodist in West Virginia, the son of a research chemist and a musician, Buckmaster is a deeply serious intellectual who had drifted for years in the left-wing demimonde: a “permastudent,” he says, in Ann Arbor, grazing from medical school to Latin and ancient Greek; an ascetic, sleeping on the floor of communal houses and grinding his own wheat to make bread; and a futurist, teaching himself unix programming and then building the Internet gateway for a vast social-sciences archive maintained at the University of Michigan. The coding skills were his ticket to Silicon Valley, where he commuted two and a half hours by bus each way to a job in Milpitas, reading Chomsky in pocket editions that looked like postage stamps in his big hands. Buckmaster has never owned a car. His disdain is at once phobic (“I don’t feel safe in them”) and political (“You see what the automobile imposes on everyone in society, regardless of whether they drive or not … If every single person on the Earth had an automobile, that would be an ecological Armageddon that the Earth would not recover from”).

Buckmaster would never have invented Craigslist. But—picture Henry Ford redesigned by Ralph Nader—it was he who took the simple machine Newmark had invented and put it on the road for everyone.

The site was limited to San Francisco. Buckmaster launched it in Boston in June 2000 and two months later in New York, Chicago, L.A., Seattle, and Washington, D.C. Then on to 34 countries. When he came on, every posting had to be manually reviewed and approved by a staffer. Buckmaster implemented a self-posting system, in which a user sends himself an e-mail and approves the listing, whereupon it is published. He expanded the categories to include child care, political and legal discussion forums, the Missed Connections list, and, in the interest of plainness, the heading Men Seeking Sex. That could not stand. After a week, Newmark, a devotee of Sex and the City, came up with the title Casual Encounters. And Buckmaster wrote the error-message haikus that zap a user who, say, tries to resubmit the same posting in a discussion forum:

a wafer thin mint

that’s been sent before it seems

one is enough, thanks

He also set up a flagging system so that offensive posts would automatically be removed through a type of group consensus—again, users proceeding without adult supervision.

“We try to get out of the way and make changes in the site to let people better accomplish what they seem to want to accomplish,” Buckmaster says—the list’s democratic mantra.

After only eleven months on the job, Newmark made Buckmaster his president and CEO. Where Newmark is goofy and chatty, Buckmaster is shrewd and courtly. He reads the Wall Street Journal and Fortune, and appears, unruffled if unshaven, in jeans and a zip-up sweater from which his bony wrists jut like sticks, at the front door of the dilapidated Victorian house that Craigslist occupies, to answer the three camera crews that show up after it’s reported that the list is featuring ads for dangerous pit bulls by explaining the site’s policy against selling animals (a policy sometimes abrogated, by, among others, my sister).

“CEO. That’s never a title I expected to have,” Buckmaster, 43, says with a slightly perplexed look. “My father’s proud. He has drawn attention to the fact that for so long I was a sandal-wearing, bike-riding, Chomsky-reading, tofu-making hippie, and here I am a CEO. There’s not really a comeback.”

“If you try to run something similar to us and subtract the sincere mission and philosophy or, worse, try to fake it, I’m sure that’s not going to work,” says Buckmaster.

The towering and intimidating CEO is Mr. Inside, while the soft and fuzzy bite-size founder is the icon. Newmark works customer service full-time (my impression is that’s fragmented time, in between feeding Bob the cat; cooing at babies in cafés; meeting Nick Lampson, a Democrat who wants to run against Tom DeLay; and going to dinners of Stewart Brand’s Long Now Foundation) and does the green room, perfecting an interview shtick that has roots in Poor Richard’s Almanack.

“The only times I’ve been in a limo I don’t want to be … ”

“I don’t believe in logic. I believe in reasoning and common sense. Logic is often misleading because logic is not human or humane.”

“My problem is that in the last decade, against my wishes, I have acquired a little bit of taste.”

“If you look at the example of my fellow nerds, once you have a comfortable living, then it’s more satisfying to change the world than to make money … Also, we nerds tend to be less interested in fancy cars or weird comb-forward hair.”

Buckmaster and Newmark sometimes differ. Newmark was uncomfortable about having a purple peace sign as the Craigslist favicon, Buckmaster went ahead and wrote the code, and now Newmark is okay with it. Their passion is essentially the same.

Buckmaster’s face wrenches in suppressed feeling when he states that there were 40 workstations set up at the Superdome in New Orleans for 20,000 people. Working thousands of miles away, Craigslist sought to shorten the lines in the Astrodome by changing its listing format, so that its page of 100 listings by headline would appear as 100 digested listings, including contact info, so that printouts could be passed around and dozens of offers considered at once. When the Red Cross balked at handling offers of help on Craigslist, on liability grounds, Buckmaster didn’t even bother to call the agency.“We saw the comments in the press, and it caused me in my mind to group the Red Cross with fema as a backward bureaucracy that is getting long in the tooth and possibly not up to the problem at hand,” he says. “It’s a very naïve reaction, and a five- or ten-year-old fear: We can’t trust something off the Internet.”

The founder’s light spirit percolates through the list—his absence of judgment, his openness, his desire to be amused, his indifference to the profit motive. Dedicated users troll the list at work for gossip or laughs, and they trust that when they offer up their souls on the list, they will gain understanding, or an audience.

Consider this anonymous screed—in the Rants and Raves category—from a Washington, D.C., woman maybe hoping her lover wouldn’t see it:

“You cannot trick me, Small Penis, into thinking you are large—by pounding away like a jackhammer. In fact, when you do this—I almost totally forget about you … It is true, Smally, that when I first saw you I did not get that certain rush of glee and pupil dilation that a giant cock will cause. I have small breasts—when I take off my shirt (I don’t even need a bra) I am sure I am not providing a moment that would be filmed in glorious slow motion with a soundtrack. Small Penis, small tits are subtle. You can be too. You will never fill me in that ‘good lord YES’ amusement-park ride way—but, remember—that is one slice of the spectrum.”

Of course, sex has always powered the Internet, and Craigslist hath many turbines. When it showed up in London two years ago, there was a media storm over the Casual Encounters list, with its frank opportunities for adultery. The Erotic Services category is a fairly straightforward list of purveyors of prostitution, who are, presumably, pleased to be freed from any reliance on pimps.

“This is something that was traditionally left up to science fiction,” says Michael Ferris Gibson, director of 24 Hours on Craigslist. “In Logan’s Run [made in 1976]—which they’re remaking this year—a guy comes home and gets on his computer and says, ‘I really feel like having a date.’ All these different women manifest. They teleport in. You also see this in sixties Utopian science fiction: relationships that were very transient and enabled by technology, and some people would say it has a hedonistic vibe to it. Well, using a system like Craigslist, it’s real.”

Yes, people also get married on Craigslist, and in Gibson’s movie, but with the list’s phenomenal growth, its Northern California book of virtues is sure to bump up against conservative sensibilities. “Do my laundry, get a blowjob … ,” a 28-year-old in Boston posted recently. She then went on with perfect pitch for American sales speech: “I’ve got what’s about 8-12 loads in the corner of my room (my laundry hamper is SO overflowed). I’ve got the washer, the dryer, detergent, and all that. I just don’t actually want to do it … If you fuck up a load, well I’m a fan of getting things done right, so you’ll either wash & dry them again, or you won’t get rewarded. I’ve got Wednesday off from work, or I guess Sunday could be laundry day.”

Or consider Kate, a 25-year-old Manhattanite, for whom Craigslist was a bust when she sought a room (people who post rooms “think they’re very easy to live with”) but was great when she sought “sane, like-minded” men for—the term of art—NSA relationships.

“I wanted to find someone who would meet my terms—that is, a nice person who wanted to have safe sex with No Strings Attached,” she told me in an e-mail. “I posted W4M [woman for man], and got 200 responses in ten minutes; I was completely floored by it! … I responded to about ten of these, and ended up meeting with four men overall, and having sex with three. I found it very easy to establish ‘ground rules’ and limits, because I had no intention of ever seeing these people again. It was very freeing! … It’s so hard for most women to go out and demand what they want in the bedroom. I think Craigslist can help to change that.”

When I showed that e-mail to Newmark, he said that the list reflects “basic American values, and freedom of choice couldn’t be any more basic.” He also likes to say that there is no real contradiction between the basic values of people in red and blue states, or the West and Islam (or in Israel and the Palestinian territories, where he has supported the group One Voice). This struck me as somewhat softheaded, Newmark’s everybody-is-good doxology. The only Muslim city on the site is Istanbul.

Some have abused the freedoms Newmark has afforded them. The child-prostitution case was a grisly one in Martinez, California, where a 22-year-old mother who is said to have advertised her own services on the list is being investigated for taking an offer for $500 to have sex with her 4-year-old daughter. Newmark assisted the police, as he has assisted New York law enforcement in tracking down apartment scams. Newmark says he spends half his time in customer service dealing with these scams. The $10 listing fee should help a great deal with this problem.

The money itself doesn’t interest Newmark. But it can’t hurt. Even if the number of New York listings were to fall to a tenth of their present number, that’s another $550,000 a month.

Buckmaster won’t confirm the figure. “We make very good livings, and the company’s business is very successful,” he says. “We’ve had the luxury of doing well and being able to follow a moral compass and not have much conflict between the two. There hasn’t been the luxury of doing that in other businesses. What’s going to come along to drop your business cost by ten- or one-hundredfold in the steel industry?”

He and Newmark can be called extravagant by no American measure. Newmark’s car is four years old. Buckmaster rides around in his girlfriend’s old Volvo. Newmark has a fancyish midsize house in the city, Buckmaster and his girlfriend share a fancyish rental in Marin. But both men seem indifferent to material things. Their indulgences have been big televisions.

From time to time, young people write Newmark with deep gratitude. “Craig … I know that you care about me,” one wrote. “You must, after all you’ve done for me … You’ve found me places to live, bought and sold a bunch of my stuff, gotten me laid, gotten me off my lazy ass and out on the town, listened to me bitch, given me wonderful advice, and taught me so much about people. Craig, I owe you so much … Please keep your list as cool as it is today … Please keep the space free of commercial ads. Please don’t sell out, Craig. I’ll love you forever, just keep it real.”

That anonymous poster was alarmed by the report a year and a half ago that Phillip Knowlton, the former staffer to whom Newmark had given shares, sold them to eBay for a reported $5 million. The two companies say they have a good relationship. Newmark will call contacts at eBay, for instance, when he needs a personal connection at an ISP to track down what he calls “a bad guy.”

Another theory goes that eBay is studying Craigslist so that it can eat it alive. It’s not the only one with an appetite. Google has recently come up with Google Base. Overseas, eBay already has Kijiji. Microsoft is trying, too. “You know there are roomfuls of guys at Microsoft, Google, and eBay thinking, How can we beat Craigslist?” Gibson says. They may never be able to replace Craigslist’s cultural cachet, but they might be more efficient and undermine the list that way.

The power of the Net could be used to sort out trustworthy from untrustworthy reporters. “I’m just trying to make newsrooms stronger,” he said.

The staff of nineteen is not going to outprogram anyone. “We’re on the trailing edge of the technology, never on the bleeding edge, given the size of our staff,” Buckmaster concedes. “But we can adopt new technology as well as anyone else can, and our users have always given us the benefit of the doubt in terms of getting bugs fixed. And our values are appealing. If you try to run something similar to us and subtract the sincere mission and philosophy or, worse, try to fake it, I’m sure that’s not going to work.

“But then, if something better comes along, so be it. People will be better off.It doesn’t have to be us. Our egos are not that big.”

In the situation comedy that Craig Newmark renders of his life, he is ruled by three looming faceless female figures: “the girlfriend,” “the decorator,” and “the nutritionist,” the last of whom issued strict orders to “step away from the buffet table” and keep his pedometer count above 8,000 steps a day. None of the triumvirate, however, told him to bite his tongue, and in England, Newmark spoke openly about the stealth media venture he has invested in to promote citizen journalism.

The power of the Net could be used, he said, to help sort out trustworthy from untrustworthy reporters, and promote stories that were important but not getting attention from the mainstream media, in which people were losing trust anyway. The epicenter of this erosion, Newmark told me when I spoke with him just before the conference, is the White House press room, which let us down over Iraq. “We need the corps to back up Helen [Thomas, the columnist, who opposed the invasion from the start].”

Newmark’s remarks were perceived as a “slam” at the mainstream media, and he was soon backtracking. We need trained journalists and editors and fact-checkers, he said. We need big newsrooms.

“I’m just trying to make newsrooms stronger,” he said when I saw him in December. Then he went on to deny that Craigslist was having any effect on newspaper revenues. “Somebody invented recently a myth that we’re hurting newspapers. I’ve done a lot of research. That appears to be an invention … We’re a minor factor.”

The more honest response is that the Internet is undermining newspaper readership, and if it wasn’t Craigslist, something else would be driving the business to the wall. But Newmark is so wedded to the idea that he is just giving people a break, he can’t acknowledge any downside to his achievement.

In fact, with all the considerable earnestness he can summon, Newmark says that his prospective journalism project (more an online ombudsman at this point than an actual newspaper) is an act of altruism. Jeff Jarvis says that newspapers need to upend newsroom culture and “face the strategic imperative of gathering and sharing news in new ways across all platforms.” That means working with citizen providers of information. “Newspapers need to find ways to share learning, promotion, information, and revenue with citizen journalists.” You heard that: revenue.

Another thing newspapers have to yield is their reservoir of trust. The big media have looked on that reservoir as a monopoly holding, says NYU’s Jay Rosen—so much so that they wrote off Craigslist in the belief that the public would consult classified ads only in a newspaper they trust. Now that the Internet is creating avenues for interactive journalism, newspapers have to accept that citizens can be trustworthy, too, or fall hopelessly behind the trend.

The response from newsmen is that reporting news is an expensive operation. John Morton, the newspaper analyst, says, “The economic infrastructure of the newspaper, I would point out, is the only one anywhere that supports mass coverage of news. In every town and city in America—only newspapers do it, only newspapers are organized to do it. However badly done, that needs to be done.” The Chronicle’s Saracevic beats the same drum: “There has been a social contract for hundreds of years—news-gathering organizations derive revenue from community advertising. Well, Craigslist is changing that equation. That symbiotic relationship is over. Who’s going to step forward to support news-gathering?”

One of the things Newmark talks about in the context of his journalism plans is a trust-and-ratings system similar to eBay’s. For my part, I wonder whether the eBay reputation ratings (in which people routinely pressure or blackmail one another to maintain good reputations) couldn’t result in virtual stonings, or shunnings of the sort that took place in the narrow-minded Winesburg, Ohios, of old (from which corporate urban life liberated us).

But at least Newmark and the other nerds are having the conversation. Most news execs are still on the sidelines.

On the last of several public-transit trips I took with him, this one on the N-Judah line, the Exploder of Journalism took the long view.

“In historical terms, the information age is just starting. Two hundred years is my time frame. I figure the decisions people make now on the Net will have effects that will resonate for a couple of centuries. Just like decisions made in the late 1600s—those effects reverberated for a couple of centuries.”

“What were the big developments in the late 1600s?”

“In politics. In scientific investigation. Intellectual thought. The arts. And—something called newspapers. My reading of things is that Fleet Street became a big deal roughly in that time frame. And”—he rolled his head back—“coffee.”

We got off near the ballpark. Having spent many hours with me, Newmark seemed finally to remember my name. But I’d noticed that none of the enthusiastic things I’d had to say about Craigslist, or the things I’d heard others say to him, seemed to reach him. There was an emotional ziplock around Newmark, the inability to take any kind of love as his own and grow from it. Maybe that’s why he started the list.

When I asked him why he couldn’t accept the love, he referred me to what he called “basically my liturgy”: Leonard Cohen. And specifically three lines from the song “Bird on a Wire” that Newmark couldn’t even say aloud: “I swear by this song / and by all that I have done wrong / I will make it all up to thee.”(Huh—that’s a lot of guilt.)

I told him my favorite lines from the song. The singer sees a beggar on a crutch, who tells him he’s asking for too much. Then he sees a woman in a darkened door—“Hey, why not ask for more?” That’s America. We move on past the guy on the crutch, we can’t count our blessings. We always want more. Or maybe it’s the human condition. I asked Newmark where he stood on that issue—did he want enough, or more?

He paused, rolled his head back. “I wish I had misbehaved more in college.”