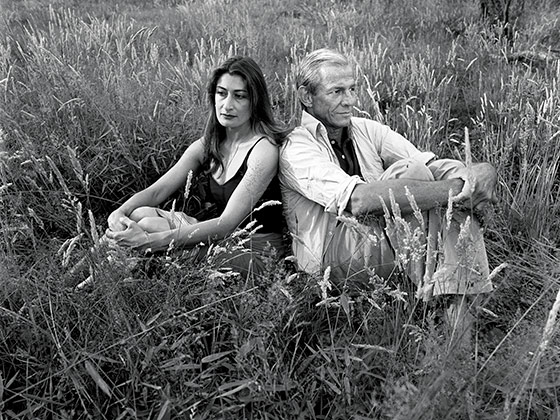

On a cold afternoon in January, Nejma Beard is walking me through her husband Peter’s vast storage space in an old warehouse building in West Chelsea. Today, Peter is in Florida celebrating his 75th birthday with the couple’s daughter, Zara, and his brother Anson. Nejma, who stayed behind with the flu, is dressed all in black. She has honey-colored hair, caramel skin, and high, regal cheekbones. She resembles Anjelica Huston, perhaps, if the actress were playing a guarded, if unfailingly polite, Chelsea gallerist.

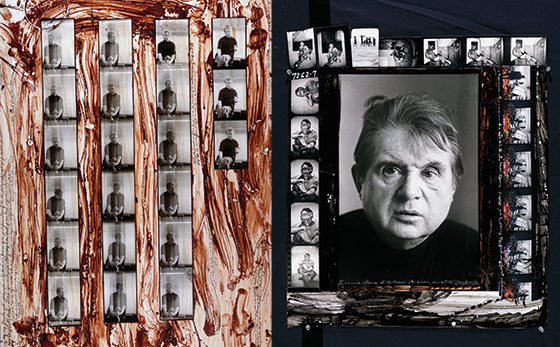

Peter Beard, of course, is the photographer alternately known for his pictures of Africa and African wildlife, his elaborate photo-collage “diaries” incorporating everything from news clippings to smears of his own blood, his photographs of international supermodels and rock stars, his leading-man good looks, and his ardent pursuit of New York nightlife. Shuttling between his ranch in Kenya and his estate in Montauk, Beard was a fixture at Studio 54 in the seventies, partying with the likes of Andy Warhol, Mick and Bianca Jagger, and Jackie Onassis. He was close with Janice Dickinson, Paula Barbieri, Veruschka, and Iman and was married to Cheryl Tiegs for five years. Although Beard has always been well regarded as a photographer, and once counted Francis Bacon as an admirer and friend, he has never reached the level of respect reserved for so-called serious artists. At times, in fact, it has seemed as if Beard were begging not to be taken seriously. “I don’t mind the word dilettante,” he once said. “A dilettante means someone who does what he loves.” He has also been famously undisciplined about his business affairs, relying on gallerist friends and party pals to manage his career, and often giving away works to friends or treating them as currency to cover bar tabs and dinner bills. Despite his considerable success, and being born into a wealthy New York family, “it’s amazing that I have gotten through without total bankruptcy,” Beard has said. A larger-than-life personality, he is by turns charming, warm, glib, arrogant, and sometimes ugly. A decade ago, he told this magazine that homosexuality was “a societal illness of every single species in nature” and that he was relieved to have met Tom Ford and seen for himself that the designer wasn’t gay. “But he looks absolutely normal!” he said when corrected.

Beard and Nejma met in Kenya, where she was born, and were married in 1986, shortly after his divorce from Tiegs. Nejma is twenty years Beard’s junior and, for much of their life together, played the role of the devoted and tolerant spouse, not involving herself with her husband’s work and allowing him his dalliances with drugs, alcohol, and other women. Recently, however, that has changed: Nejma is now actively seeking to secure Peter’s legacy—and his financial future. On our tour of Beard’s storage facility, nearly everything she says reflects a desire to lift her husband’s status in the art world. She talks about how this should be Peter’s big moment, given the environmental message of his work. She has hired a consultant to help her court museum curators who might mount a major Beard retrospective. She prefers to sell directly to collectors now rather than work with galleries, to more carefully control the value of his work. Perhaps most controversially, for financial and legacy reasons, she has taken steps to reclaim, or claw back, some of the works Beard has given away over the years, a move that has infuriated some of his old friends. “She’s trying to control the purse strings and keep him on a short leash,” says one friend. “She’s eager to establish him before he dies as an important artist. That’s going to be her nest egg.”

Starting with The End of the Game, Beard’s seminal 1965 work featuring beautiful yet haunting pictures of starving elephants in Kenya’s Tsavo National Park, Nejma is also republishing Beard’s out-of-print books, and some of his individual works, in high-priced, large-format limited editions. “Every artist needs an editor,” she says. “I regularly go through Peter’s contact sheets and mine them for images I think he may want to use.” Nejma is also exploring merchandising opportunities with an environmental tie-in. “Peter wants to do wallpaper. It’s just a question of finding the right company to do it with. We’re also looking into limited-edition rugs and floor-length scarves.” More than once, Nejma affectionately refers to her husband as “P.B.,” as if she’s the executive producer and he’s the talent. Anything he does, she says, would have to reinforce and not undermine his work’s sense of natural-world authenticity. “This man has broken bones to show for what he’s done. This isn’t someone running around a garden with a butterfly net.”

Thanks in part to her efforts, the art market is experiencing something of a boom for Beard. Last year, in London and New York, two of his pieces set records, each selling for more than half a million dollars. Even while she seeks to further raise Beard’s profile, Nejma remains wary of media attention. She won’t comment on her alleged attempts to retrieve some of his works and won’t let Peter be interviewed in person, lest, presumably, he says something she regrets, given his freewheeling mode of expression. Her new policy is written questions only, unless it’s with friends like Alec Baldwin, with whom Beard held forth on a podcast last year. “He really deserves to be out there now, but he just doesn’t play the game the right way,” Nejma says. “His antics have been chronicled to death in the press. But now that the circus has left town, so to speak, he has the peace of mind to concentrate on his work.”

A few days after Nejma and I met, I asked Beard, by e-mail, what he thinks about the new focus his wife has brought to his work. “Now that art is almost entirely a commodity,” he wrote, “I’m glad to be, shall we say, commodious.”

Peter Beard was born a New York aristocrat, heir to a railroad fortune on his mother’s side of the family and a tobacco inheritance on his father’s. Educated at Buckley, Pomfret, and Yale, he made his first trip to Africa when he was 17, taking photographs with a Voigtländer camera his grandmother had given him. (Some of the pictures he took that summer would end up in The End of the Game.) On a return trip to the continent in his twenties, Beard met and befriended Karen Blixen, a.k.a. Isak Dinesen. In the mid-sixties, he purchased Hog Ranch, a tent encampment outside Nairobi, partly because it abuts the land that inspired Dinesen to write Out of Africa. “I made a life for myself in Africa that was as far as you could possibly get from art school at Yale,” Beard told me by e-mail.

By the time he followed up The End of the Game with Eyelids of the Morning, a study of crocodiles, in 1974, he had begun doing fashion work for Vogue, and had shot the Rolling Stones as they toured for Exile on Main Street. He also started creating his multilayered, mixed-media diaries—an intensely personal and original style showcased in an exhibition at the International Center of Photography in New York in 1977. Although observers saw ecological themes in Beard’s work, he resisted being labeled an environmentalist. His worldview had more to do with the brutality of the natural world, the violent nature of existence, and the folly of man. “Conservation,” he once said, “is for guilty people on Park Avenue with poodles and Pekingeses.”

Beard became a staple of the international art and party scene. He bought his Montauk property near Andy Warhol’s place in 1972 for about $135,000 (it’s easily worth more than $20 million today) and photographed Truman Capote, Mick Jagger, and a skinny-dipping Jackie O. on the premises. He befriended Bacon, and the two became close enough that Bacon painted Beard’s portrait more than once. He met Iman in Africa and frequently took credit for launching her modeling career. At nightclubs, he’d turn up regularly with an entourage of ten or twenty. His virile safari style inspired designers from Michael Kors to Tommy Hilfiger. (In a grisly episode that seemed all but preordained, he was trampled by a charging elephant in Kenya in 1996; the video, if you can stomach it, is available on YouTube.)

If Beard cared at all about managing his career or finances, he didn’t seem to show it. Photographer Sante D’Orazio, a good friend since the late eighties, remembers visiting Montauk and finding the phone dead and stacks of unopened bills beneath it (even now Beard doesn’t use a cell phone). Another time, D’Orazio followed Beard into a dark shed and found himself walking over negatives covering the ground beneath him. “Just all open, exposed, not wrapped in anything! He says, ‘Oh, don’t worry about it. I’m gonna get around to it one of these days.’ ” Once D’Orazio offered to print some negatives of Beard’s, thinking Beard lacked the wherewithal to do it himself. “The first thing he does is, the mailman comes to pick up the mail, and he gives him a print! I’m like, Holy shit. That’s how he was with everybody.”

Nejma is the oldest of seven children born to a conservative Muslim family. Her father was a high-court judge, now retired, and her mother is an amateur champion bridge player. “They brought us up strictly, and I learned the hard way to appreciate that,” Nejma says. After studying anthropology at the University of Sussex, Nejma traveled in Europe for a time. When she returned to Kenya, friends introduced her to Beard, and she quickly fell in love. “He was outlandish—everything to him is a green light—but so incredibly refreshing,” she says. “He has a sort of magic to him that when he concentrates his attention on you, it’s like the sun suddenly coming out.” She was also smitten with Hog Ranch. “It has the elegance of simplicity and, to use one of Peter’s favorite words, authenticity. You sleep in tents that are wide open to the animals and the elements, and you wake in the morning to birdsong.”

Beard said later in an interview that he was equally taken with Nejma, realizing immediately “that this was the only person I could be married to—the Africa connection was essential.” Zara was born in 1988, and during their early years together, the family lived mainly in Africa, making regular trips to Montauk. But Beard had never been wired for monogamy. While Nejma turned up in Beard’s work like any number of women, she was not his central muse, and at times Beard seemed to live a life completely apart from her and Zara. In a 1996 Vanity Fair story, he emerged from his tent at Hog Ranch with not one but four or five Ethiopian girls. “We were very cozy,” he said. Marriage, he said at the time, was a ridiculous institution. “Biologically it’s very unnatural. It’s masochism and torture the way it’s been organized.”

In 1993, Beard struck up an informal partnership with Peter Tunney, an investor whose Soho gallery, the Time Is Always Now, became the site of a nonstop party hosted almost nightly by Tunney and Beard (and almost never attended by Nejma). “It was fashion and art, creativity, models, socialites, and drugs,” says Jeffrey Jah, the nightclub investor, who attended several of the events. “People were crazy.” Over the years, Tunney became Beard’s de facto financial manager. “If Peter needed money, I gave him some money,” Tunney tells me. “We literally spent every day together.” No one really kept track of the work Beard created during his nine years with Tunney. “He didn’t want to do editions or stuff like that,” Tunney says. “He wanted each piece to be a living, breathing work of art.” As one close friend of Peter and Nejma’s recalls, “A lot of people took advantage of people, at his studio at night. ‘Peter, I like that!’ ‘Oh all right, you can have it.’ That’s a double whammy for Nejma, because she didn’t like that activity, and he’s giving away the art.”

By 1996, the Beards were reportedly divorcing, with Nejma accusing Peter of molesting Zara. Peter had claimed this was just a tactic to get custody, and in response Nejma told Vanity Fair that “Peter’s problem always has been too many drugs.” According to Tunney, Nejma stepped back into Peter’s life shortly after the elephant attack. “One thing the accident did do was ground me,” Beard later said. The couple reconciled, Beard left Tunney’s gallery, and the Beards took Tunney to court. Tunney countersued, the cases were settled, and neither side will discuss the details. Tunney notes that Nejma’s return happened to follow a wildly successful show of Beard’s work that he and Peter mounted at the Centre Internationale de Photographie in Paris.

“I think it’s fair to say that Nejma probably thought we were having too much fun, not doing things professionally enough, not knowing where the money was going,” Tunney says now. “I was basically just plowing all the money back into the whole operation. It was an enormously expensive thing. But just when it was becoming a substantial thing, Nejma came in with the lawyers and said, ‘The party’s over, I’m in charge.’ And Peter said, ‘There’s nothing I can do.’ ”

Nejma insists she never wanted to manage her husband’s business affairs but that the role was thrust on her. “I was just a kid when I met him, and I thought he could take care of me. When I first took over, I hardly believed I could do it. But I had to—it was the only way his work was going to flourish.”

Drawing on advice from friends like Peter MacGill of Pace/MacGill gallery, Nejma started putting a halt to the sale of Peter’s artwork to better control it, ending his relationships with his galleries, including Tunney’s. Two friends say she put Beard on an allowance. He resisted the new measures at first, telling one friend he was going “on strike with Nejma” and that “she took away the keys to the car and we aren’t speaking and she won’t send me any money.” Beard quietly sold a few works through the art dealer Elizabeth Fekkai, until Sotheby’s called Nejma to authenticate one of the pieces and Nejma exploded. Nejma says Beard eventually came around under pressure from others in his inner circle, including his lawyer Michael Stout and his brother Anson, a retired executive with Morgan Stanley.

Nejma’s efforts to manage Beard’s career would have probably gone unnoticed outside a small circle were it not for the claw-back attempts. Last year, Jah, who has comped Beard and his entourage on countless nights over the years at his clubs, was approached by someone close to the Beards about a work of Peter’s—a portrait of Francis Bacon that had been displayed for years in the VIP room of Lotus. Beard had spent so many wild nights at Lotus that the VIP room, accessible only by a keypad with a secret code, had been named the Peter Beard Room. The portrait had been in Jah’s possession since the club closed in 2008. Now he was being asked to give the portrait back.

Jah, according to two friends, could hardly believe it. He won’t comment on the specifics of the dispute, but he suggests that the burden of proof rests with the Beards. “If Peter loaned someone a piece, there should be an agreement stipulating the terms of the loan,” he says. “The problem is, Peter made a lot of transactions that were not in his best interest at times when he did not have money, and probably a lot of those transactions were done without documentation.”

Nejma won’t discuss Jah by name, but she insists she and Beard are only interested in reclaiming works that were clearly loans. “Anyone who owns Peter’s work legitimately,” she told the Post in November, “has nothing to worry about.” In addition to the Jah work in question, Nejma is said to have reported several other pieces to the Art Loss Register, a database of lost and stolen art used by insurers and law-enforcement agencies (if the Beards can’t reclaim the works, listing them this way makes them difficult to sell). People whom Nejma has allegedly asked to prove they legitimately own their Beard works include longtime Jah and Beard friend Jay McInerney, banking heir Matthew Mellon, and restaurateur Nello Balan. (Balan and McInerney have said they own the works legitimately; Mellon could not be reached for comment.) Nejma insists that if a work is unsigned, the way Jah’s Bacon portrait is said to be, there is no way Beard would have given it to someone to keep. “When Peter finishes a work, he always signs it.”

Practically speaking, tracking down every errant Peter Beard artwork may prove impossible. In Manhattan, Amaranth, Nello, and Cipriani, to name just a few places, have walls jammed with Beards. “Half the bars in Montauk have Beard photos on the walls,” says one old friend of Peter’s. “Not to mention in the south of France. He’d use a photo to pay off a $20,000 bar bill.”

On Beard’s 75th birthday, Zara, now a college student, presented her father with a 30-page birthday card she’d made. His 40th-birthday celebration, in 1978, had been at Studio 54, and his 65th at Downtown Cipriani. This time around, “we went to see the Annie Leibovitz show at the Norton museum,” Beard told me in an e-mail, “which was surprisingly great. Then we went to the Steve Rubell memorabilia auction. Anson bought me a copy of Andy Warhol’s Exposures signed by Andy to Steve.” Inside, there was a double-page spread of Beard in New York, smoking a cigarette, looking like a young movie star. He says the photo was taken the day after a 1977 fire destroyed his millhouse in Montauk, taking with it years of his diaries. At the time, Beard refused to be sentimental about the loss. Now things are different. “It’s a book chock-full of dead friends,” he wrote. “So you can’t help thinking of all the things that have come and gone—and somehow still stayed.”

A year ago, D’Orazio saw Beard out on the town as usual, the only notable difference being he’d just had a hip replacement the previous day. (“He’s Tarzan, that’s for sure,” says D’Orazio. “He’d take you out on safari, and he’d never get hurt, but you would.”) “As recently as a couple weeks ago, I saw him out on the town with two young admirers,” says another friend. “The only time I see Peter is at Bungalow at three in the morning.”

Nejma’s attempts to manage Beard’s career have cost him several relationships. A number of old friends see her as ruthless and meddling, seizing control of her husband’s business affairs and trying to profit from his work in a way Beard himself never seemed to care about. “She doesn’t like anybody who is Peter’s friend,” says one person in question. Nejma’s supporters, meanwhile, say she has done Beard a great service. “Nejma is the only one who has always had his back,” one friend says. “The good-time party people always move on. With Nejma, he can take his rightful place. He can have a legacy.” At heart, friends say, Beard and Nejma complement one another. She loves his unfettered passion, even if it sometimes infuriates her, and he loves her stability and good sense, even if those qualities sometimes madden him. One longtime friend says Beard and Nejma seem to be closer now than they have ever been. “Over the years, I’ve seen it all—her being cranky at parties and so on. But they seem to be at a calm point. He speaks highly of her, which is certainly not true of his other wives.”

Beard won’t comment on his romantic relationship with Nejma. He will only say that he’s grateful, and proud, of what she’s done for his career. “I am happy to be independent of the whole system,” he writes. “Nejma has stripped away almost all the complications of the art industry. And with zero business or art-world credentials. What she had instead—and has—is a unique combination of taste, common sense, integrity, and imagination. I’m in awe of what she’s accomplished.” At the same time, one can apparently only tame Beard so much. In the very same e-mail he wrote: “An artist who goes around proclaiming that the art he’s making is art is probably making a serious mistake. And that’s one mistake I try not to make.”