The news keeps coming, each item worse than the one before. New-home sales fall 26 percent nationwide; the U.S. economy loses 17,000 jobs in January; Wall Street write-downs cross the $100 billion mark. Sure, the technical definition of a recession is two or more consecutive quarters of negative growth, but with headlines like that, and last week’s word that fourth-quarter GDP was up an anemic 0.6 percent (in other words, all but down), does anyone really believe that the U.S. economy is not on the precipice, or already over the edge? The prospect of a national economic downturn raises all sorts of troubling issues, of course. But from an entirely parochial point of view, one question stands out: What’s going to happen to New York?

Perhaps the best way to answer that is to look at what happened the last time the city went into a prolonged funk. Not the 2000 NASDAQ crash and the post-9/11 malaise, both of which, bad as they were, came and went comparatively quickly. We’re talking about an all-out, multiyear five-borough slump, one which your average 30-year-old Wall Street analyst, say, is unlikely to even remember: the sad stretch from 1989 to 1992, when the median home price in Manhattan dropped by more than a quarter, construction declined by a third, and the city lost one-tenth of its jobs.

It all started, of course, on Wall Street. On Black Monday, October 19, 1987, the Dow Jones index, for reasons still being debated, fell 508 points, almost a quarter of its total. (The current equivalent, for comparison’s sake, would be a 3,200-point loss on one day.) The drop turned out to be a “black swan event,” a weirdly poetic economist’s term meaning, basically, a fluke (though few people remember it, the Dow still eked out a positive finish for the year). Still, the hiccup seemed to foretell the instability to come. Over the next two years, with the economy perceived to be overheating, the Fed repeatedly jacked up interest rates, which made bonds and T-bills sexier than stocks, which triggered an epidemic of unscrupulous bond peddling, which further destabilized the market—leading to a slowdown. (If that all sounds disturbingly like the recent subprime-debt mess, well, that’s because it is. But more on that later.) And a slowdown on Wall Street, which provides over 20 percent of the city’s cash income, spells a slowdown for New York.

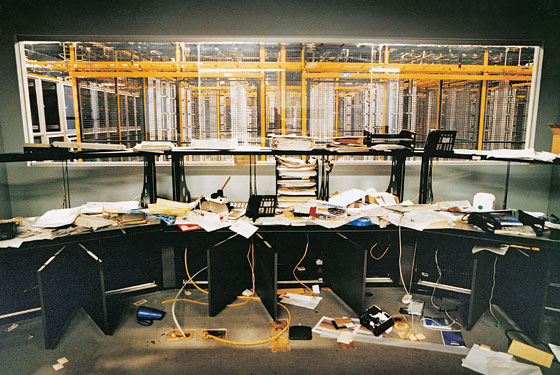

The city’s economy, meanwhile, was already primed for problems. In the mid-eighties, the vogue for mergers, acquisitions, and leveraged buyouts meant that companies began relentlessly shedding redundant employees to spruce up the bottom line. “New York is a bit uniquely affected by trends in management-consulting practices,” says James Parrott, chief economist at the Fiscal Policy Institute. “CEOs were easy prey for consultants who sold them on the easiest way to the profits: Get rid of middle management. We have a lot of corporate HQs, so it hit us hard.” At the same time, the personal computer was revolutionizing the way companies do business—processing, which used to require a clerk and often a courier, was now done with the push of a button. Soon enough, legions of back-office staff were being let go as well. Wall Street alone saw 16,000 layoffs in the two years before the recession even began.

Just as Wall Street and other firms were trimming personnel, another problem was taking shape: A glut of new office space, mostly in midtown, was coming onto the market, forming a bubble in commercial real estate. Thanks to a tweak in regulations allowing savings-and-loan companies to finance commercial construction, banks nationwide got into the business of underwriting skyscrapers. Earlier, City Hall had fanned the developers’ enthusiasm by temporarily throwing certain high-rise zoning restrictions out the window. New York’s skyline was changing like it hadn’t since the twenties. By the time the construction spurt was over, demand couldn’t keep up with supply: Lower Manhattan’s office vacancies climbed to 17.8 percent, among the worst rate in the nation. Stuck with empty towers, the developers began defaulting, taking underwriters down with them. Employment in the architectural industry dropped 23 percent, from 8,424 jobs in 1989 to 6,482 in 1991; the vaunted skyscraper design firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill halved its staff. The mood in the trade was nothing short of apocalyptic. “The high-rise building,” wailed one despondent architect to the Times. “It’s vanished … It has disappeared.” Construction, which employs far more people, dried up correspondingly.

The residential sector, meanwhile, suffered a parallel glut of co-ops newly converted from rentals. “There were some tax-law changes in the mid-eighties that made it very profitable for landlords to convert their buildings,” says Fred Peters, the president of Warburg Realty. Profitable, that is, until the supply reached saturation point just as leaner times on Wall Street began to drain the demand. The shock was sudden and painful. “It just stopped,” remembers Peters. “The first half of the year was just like ’88, a banner year, and then it just stopped. The Japanese kept buying for another year. But then it just ran aground.” In a swift reversal of the conversion boom, people who couldn’t sell their apartments started trying to rent them out, often to no avail.

Things started to get really scary when some of the S&Ls that financed the co-op conversions went belly up. For the first time since the Great Depression, it was possible for perfectly solvent buyers to get stuck with a virtually worthless property. In one of the most extreme cases, the FDIC liquidated the assets of Silverado Savings and Loan, a collapsed Denver outfit, by seizing a 26-story co-op near Lincoln Center it had co-owned. Across town at Tudor City, owner Time Equities couldn’t cover the complex’s underlying mortgage and taxes (not to mention utility bills and staff costs), and ended up giving it away, unit by occupied unit, in a jaw-dropping fire sale: In 1992, if the new owner were willing to assume the accrued debts, a Tudor City one-bedroom could be had for $3,500. In the East Village, Lower East Side, Upper West Side, and Harlem, people abandoned buildings outright: After Mayor Dinkins raised property taxes, property owners began selling to cut their losses at a rate not seen since the Bronx Is Burning days of the seventies.

In the meantime, a new issue weighed heavily on the economy—the looming Gulf War. With GDP slowing and consumer confidence down, the Dow sputtered, and another round of Wall Street layoffs and defections followed, this one reaching much higher up the food chain. “In 1990,” remembers one former investment banker turned hedge-fund manager, “my compensation went down by a third. Obviously, you think about leaving. I decided to stick around, but a lot of people got out. They kept saying, ‘It’s just not fun anymore.’ ” Many traders and bond salesmen, having amassed vast fortunes in the eighties, chose 1990–91 as the moment to retire. Others had that decision made for them in the wake of bond-trading scandals.

The third tent-pole that had propped up the New York economy—along with Wall Street and real estate—was tourism. In 1989, the estimated economic impact of tourism on New York was $12 billion, more than the combined financial-industry salaries for the year. But by 1990, it too was flagging, thanks to the war, the cost of oil, and New York’s persistently high crime rate (that was a year of 2,262 murders, 18,000 subway felonies, and Brian Watkins, the 22-year-old Mormon tourist who was knifed to death in a subway station).

So many jobs were dependent on out-of-city visitors and free-spending trader types that unemployment spread quickly throughout the city. Retail shed 50,000 jobs, with restaurants and food sales among the hardest-hit sectors. “The Dow Jones was so low,” half-jokes Keith McNally, whose Tribeca-defining Odeon was arguably the nexus of the prerecession boom, “that we could no longer offer fresh pepper. The salad bar was never the same.” Weak demand, combined with an increased hotel tax, started putting hoteliers out of business, too. The airline industry reeled from the back-to-back bankruptcies of Eastern and Pan Am Airlines. Publishing, a $14.9 billion business previously thought to be “recessionproof” (Random House, Simon & Schuster, and Viking all grew through the Great Depression), fell victim to an unrelated dependence on the megastore concept. Legal and accounting services, which feed off Wall Street, began mass layoffs. Manufacturing employment saw its worst losses since World War II. By the time the dust settled, 361,200 jobs—precisely 10 percent of the total workforce—would be gone.

Nationally, the recession lasted only nine months, from July 1990 to March 1991. But the city’s ringside seat to the Wall Street follies meant that the downturn here began earlier, hit harder, and stuck around longer. Things started to turn around in December 1991, when the Fed let loose with an emergency discount-rate cut of one full point (bringing it to 3.5 percent) and didn’t raise rates again until 1994. “When you can borrow cheaply, you can leverage the hell out of everything,” says Parrott. In Japan, interest rates were even lower—about one percent—and American businesses began borrowing in Tokyo to finance deals in New York. Within a year, a yen-fed Wall Street was back up and staging a kind of jobless recovery: From 1992 to 1993, while the region lost another 67,000 jobs, financial-sector salaries jumped by a gaudy 45 percent, to $164,000 on average. With big bonuses coursing through the city’s financial veins, New Yorkers started spending again. Broadway posted a 22 percent jump in ticket sales. Hotel occupancy crawled up. Stores reported a record Christmas season.

By 1994, lured by the finally bottomed-out rents, national stores began moving in on Chelsea and the midtown district, making Sixth Avenue between 14th and 34th the generic (but lucrative) strip mall it is now. Barnes & Noble, Bed Bath & Beyond, and CompUSA all opened new stores in Manhattan. A Times article from the summer of 1994 titled “New York Area Climbs Out of Recession” mentions the first outpost of a novel “Starbucks expresso [sic] bar” in Westchester County.

Real estate was the last to recover—the aftermath of the 1990–1992 fire sales continued to depress the market well after the financial meltdown that triggered those sales was over. According to Barbara Corcoran, a one-bedroom postwar co-op on the Upper East or Upper West Side that might have cost $275,000 in 1988 sold for around $160,000 at the end of 1993. By 1994, however, real estate had already embarked on the storied upward climb that would remain virtually unbroken until now.

The moral of the story appears to be that Wall Street money got us into hot water and Wall Street money got us out. And that raises New York’s most pressing question for the rest of 2008 and beyond: Will this time be better or worse than last time?

Between 1989 and 1992, Manhattan home prices dropped by more than a quarter, construction declined by a third, and the city lost one-tenth of its jobs.

Let’s start with the more sanguine of the two scenarios. On Wall Street, those who say we’ll be better off this time point out that there has been no panic-inducing, confidence-shaking single-day crash like Black Monday. Yes, the Dow has already sunk below its 2007 low, bulls allow, but the market, at press time, was still a hair above where it was this time a year ago. And the federal-funds rate is at 3 percent, the lowest it’s been since 2005, which should make it easier for banks to start lending again, which should, in turn, help spur a recovery. Optimists also say that the subprime crisis, brutal as it has been, is limited to the housing and financial sectors and won’t infect he rest of the economy the way the M&A-induced layoffs and the unsound lending practices of the eighties did. Some mention that the city has reduced its historic dependence on the securities industry altogether. The Bloomberg administration has led a drive to diversify New York’s economy, and, indeed, over the past four years, 166,650, or 81.7 percent, of the 204,090 newly created private-sector jobs were in service, tourism, film, and other non-financial industries. City Hall has also, in an unprecedented move, squirreled away $2.5 billion of last year’s surplus to carry us through 2009. “Although I am certainly concerned about contraction of revenues compared to what I’ve been forecasting next June, I’m not in tailspin,” City budget director Mark Page says. “Revenues can slip $2.5 billion before I run a deficit.”

In terms of construction, optimists say, the current building boom is no match in volume for the commercial-building craze of the mid-eighties, so a major contraction there is unlikely. Another key difference between now and 1989 is that developers and contractors have found an enthusiastic co-sponsor in the government. The city, the state, the MTA, and the Port Authority have tremendous capital budgets compared with the eighties, and they’re using them. From the two brand-new stadiums (and a possible basketball arena in Brooklyn) to subway-line extensions, the city is awash in major civic projects. Even Bruce Ratner, who’s using the atmosphere of economic uncertainty to try to expedite Atlantic Yards before the sky falls, is likely just being clever: His financiers at Goldman Sachs had a banner year and appear to be uniquely unaffected by the bad-debt debacle.

Glass-half-full types also note that the New York residential-real-estate market looks better than it has a right to, given the disastrous nationwide slump. It’s almost impossible to imagine the 1990 co-op bust scenario replaying itself today. Co-ops are entrenched and in short supply (there were just two conversions in Manhattan in 2006). Because of the high cost of the average New York apartment, relatively few homeowners here are directly affected by the subprime mess or risk foreclosure (subprime loans were made mostly to high-risk buyers at the low end of the market). There’s also an international angle to New York real estate that wasn’t there last time around: Driven by the cheap dollar, foreign buyers were behind 15 percent of our apartment sales in the last quarter of 2007. The Irish, Russians, Chinese, Saudis, and many others have all been enthusiastically investing in Manhattan pieds-à-terre, and especially in new construction. And unlike in the late eighties, crime is low and families have been staying in the city, instead of moving to the suburbs, when they have kids. One heartening lesson of the early-nineties housing bust, notes Warburg’s Fred Peters, is that unlike in many other American cities, the middle class did not decamp to the suburbs en masse. If the pull of the city proved strong enough in an era of six murders a day, it will be more than enough in the current climate.

In retail, according to the sunny view, the most glaring difference between then and now is the emergence of the ultraluxury market. The recent historic growth at the top end of the economic ladder, or so the theory goes, has created a kind of recessionproof super-spender. What’s more, New York itself has become a global luxury brand, optimists say—a place where people come, from New Jersey or Dubai, to conspicuously consume. That’s true on the retail level (witness the out-of-town throngs in Times Square on a Saturday afternoon), and it’s true on the corporate level (see Saudi Prince Alwaleed’s bailout of Citigroup).

But then, of course, there is also a dimmer view of our immediate economic future. In this scenario, the subprime mess wreaks havoc. First, it continues to drive down the Dow, as unwelcome surprises continue to crop up (like last week’s scare that bond insurers MBIA and Ambac may buckle under the weight of the $1 trillion in mortgage debt they’ve guaranteed for corporations and hedge funds) and unnerve investors, who hate nothing more than uncertainty. Second, it continues to decimate the big banks, which continue to slash bonuses and lay people off, sucking millions out of the New York economy. Despite the efforts to lessen New York’s dependence on Wall Street, economic Cassandras note, banking is still hardwired into the heart of New York. In 2007, Wall Street capital gains and wages accounted for 25 percent of New York State’s (state’s!) growth. Another frightening factor? After Black Monday, the effects of a Wall Street contraction took two years to spread through the system. This time, “I think layoffs will come sooner,” says Byron Wien, chief investment strategist at Pequot Capital. “Because the traditional structure of mergers and acquisitions is less profitable, you had a lot of traditional-banking people wanting to go into equity and hedge funds”—the areas that are the most vulnerable now. Wall Street already lost scores of jobs in 2007, mostly from the subsectors Wien mentions. If it tightens its belt further, 1989-like numbers aren’t hard to see.

Commercial real estate also affords a bearish view to some observers. Right now, many developers are adopting a wait-and-see attitude before breaking new ground, and a few recently green-lighted projects are already on the skids: Billionaire and likely mayoral candidate John Catsimatidis, whose Red Apple Group is developing a two-block complex on Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn, is putting the brakes on the project until the lending situation shakes itself out. Even more ominously, some developers who borrowed billions to buy or spruce up major properties find themselves unable to refinance as their loans mature (take, for instance, Harry Macklowe, who last week was forced to hand seven midtown towers, including the GM Building, over to Deutsche Bank). Finally, despite its developer-friendly intentions and healthy capital budgets, city government is proving an unreliable partner. Every big civic project with state or city money in it (save the new baseball stadiums, both well under way) recently took a budget cut. The funding for such much-heralded undertakings as the Second Avenue subway, Santiago Calatrava’s path terminal, and the 7-train extension is in question. Perhaps most surprising, after two years’ worth of adoring press, the dome-shaped Fulton transportation hub—touted as downtown’s answer to Grand Central—is out entirely. Until banks regain the confidence to begin lending again, commercial and civic construction in New York could grind to an almost immediate halt.

The pessimistic line on residential real estate is simple: We’re overbuilt and overpriced. By some estimates, tens of thousands of newly built condos could sit on the market. If the lack of Wall Street bonuses saps demand, we might see quite a few of these condos turned into rentals by 2009, which will, for the first time in ages, make renting a preferable alternative to owning (and speed up the price decline, in a self-propelling downward cycle). The consensus among top real-estate economists quoted in this magazine in September cites the worst-case scenario for New York residential housing as a 5 percent correction this year, followed by a nosedive of 18 percent, in reaction to the sure-to-be-anemic 2008 data, in 2009. As for the theory that foreign pied-à-terre hunters will keep the prices afloat, one need only look back to 1989. Back then, Japanese buyers single-handedly propped up a dead market a year past its expiration date—until they didn’t, which made the ensuing drop all the more steep and painful. Pessimists note that Fed chairman Ben Bernanke and his counterparts abroad have been under pressure to coordinate rate cuts to stimulate the global economy in unison—a move that could bring the dollar into closer alignment with those countries’ currencies, and put a jarring end to the foreign buying spree in New York.

As for retail, the ultrahigh end of the market, influential as it is, only accounts for so much spending. A national or, worse, global recession is sure to shorten the lines for The Lion King and leave scores of hotel beds open. And New York as a global superbrand is bound to be less appealing if the store starts running out of money for glass condo towers, transit hubs, and other glitzy developments.

So what’s it going to be? A slowdown or a meltdown? And how long will it last? Most economists agree that the long-term prospects for both the U.S. and New York economies are good. But shorten the time horizon to six months, or even a year, and few experts predict much of anything good. It’s going to take at least that long, the consensus seems to be, for the subprime-mortgage mess to be absorbed and filtered out by the system. Beyond that, no self-respecting pundit could really say what will happen. Which is not to say that many won’t try.

SEE ALSO

• The Upside to the Downside

• The Everything Guide to Belt-Tightening

Additional reporting by Kari Milchman.