What is, or was, Tucker Carlson? The prevailing view in the mainstream press is that he was a sneering bigot who peddled crude resentment in a cynical quest for wealth. But a more subtle, even flattering interpretation has also emerged. What if Carlson was a rebel against the Establishment? What if he was defying the pieties of his own side and even, in his own peculiar way, bringing us closer to a more just and humane world?

A version of this concept can be discerned in Ross Douthat’s argument that Carlson advanced a “realignment,” in which conservatives grew more distrustful of authority as liberals became more reliant on it. A more fulsome iteration of the case comes from the left-wing American Prospect, which lionizes Carlson as a tribune of the workers.

While the Prospect does not dispute the charge that Carlson has been a bad boy, it casts the overall thrust of his worldview as progressive:

But Carlson’s insistent distrust of his powerful guests acts as a solvent to authority, frequently making larger-than-life figures of the political establishment defend arguments they otherwise treat as self-evident …

Tucker’s willingness to challenge and mock ruling elites went alongside an obsessively nativist message that alienated viewers who might otherwise have embraced his populist perspective. His popularity with a wide audience begs the question why other nightly news shows that attacked him didn’t raise the same critiques, without the nativism …

Tucker Carlson Tonight was an outlier in corporate-owned cable news, which is typically hostile to independent critiques of executives and political elites. The show declined to play the gatekeeping role that many of Carlson’s detractors demand of mainstream media platforms.

The problem with this analysis is not just that it downplays the importance of Carlson’s bigotry vis-à-vis his “progressive” views. It’s that seeing his version of populism as a strain of progressivism at all is a misapprehension. To the extent that Carlson is breaking with traditional conservatism, he is breaking to its right, not its left.

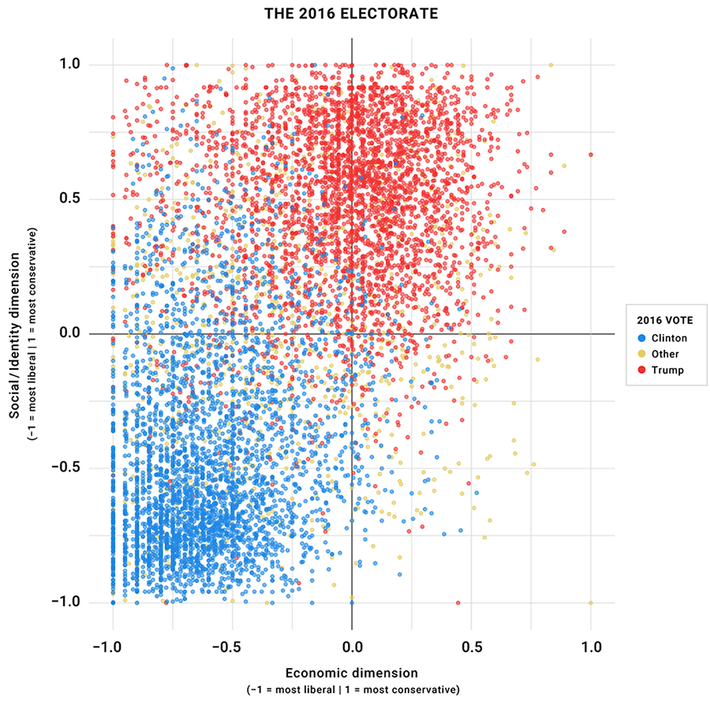

The source of this confusion is that political elites really do share some bipartisan tendencies that go unexamined. Rich conservatives are far more right-wing on economics than Republican voters are, while rich liberals are far more socially progressive than Democratic ones. The political elite has converged on the idea that “socially liberal, fiscally conservative” is the natural middle ground in American politics when the reality is the opposite. There are far more voters who have socially conservative, fiscally liberal views than vice versa. The socially liberal, fiscally conservative quadrant that’s so popular in greenrooms is nearly empty:

Furthermore, it is also true that Carlson employs more anti-free-market rhetoric than most of his conservative colleagues do. He lambastes multinational corporations and even the free market itself. In 2017, he gained some notoriety by telling President Trump that his health-care repeal bill mainly hurt his own voters.

So it may seem that Carlson is occupying the socially conservative–fiscally liberal quadrant and that his offensive utterances are the price to pay for his telling truth to economic power.

But Carlson isn’t really innovating anything by casting himself as an enemy of the powerful, financiers, or globalists. Bashing these targets on behalf of the working folk is a hallowed tradition in reactionary politics dating back to George Wallace or (perhaps the closest parallel to Carlson) Father Coughlin. Even in modern Republican politics, it’s hardly unusual for conservatives to depict themselves as populist tribunes. Even before Donald Trump perfected this pitch, George W. Bush was running as a brush-clearing good ol’ boy and John McCain made supposed working-class tribunes Sarah Palin and Joe the Plumber the mascots for his closing message that Barack Obama stood for the elite.

There are two main differences between right-wing economic populist rhetoric and the left-wing variety. One is simply whether it is genuine. Right-wingers may recognize the need to attract a broad coalition to their program with populist rhetoric but for the purpose of binding it in a political coalition with reactionary business owners. Carlson fits this profile to a T: His private messages reveal him as holding his own audience in contempt and manipulating them for ratings.

Another characteristic of right-wing populists is that, even while attacking capitalist elites, they simultaneously attack racial or ethnic minorities, depicting the two as acting in alliance. The most historically famous example is the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, which — despite employing terms like socialist and workers and plenty of rhetoric attacking global capitalists — directed its strongest anger against Jews and other “foreign” elements.

This describes Carlson even more precisely. He rails against immigrants, minorities, and foreign countries in general. He explicitly endorses the “great replacement theory,” a white-supremacist belief that an elite cabal is using immigration to undermine the “native” population. The concept that the nation is being undermined by an elite global conspiracy is an echo of Nazi themes.

Even Carlson’s famous moment of criticizing Trump’s Obamacare repeal counties — his most direct attack on the Republican economic program — did not question the premise of reregulating the insurance market and cutting subsidies. Instead, Carlson complained that Trump’s plan hurt the wrong people. (“A Bloomberg analysis showed that counties that voted for you, middle-class and working-class counties, would do far less well under this bill,” he said.)

Notably, Carlson let Trump off with a vague promise to protect his people in the final bill, a promise Trump predictably ignored. Even more notably, the Republican who ultimately drove a stake through Trump’s health-care rollback was not some self-styled populist but John McCain, Carlson’s neocon Establishmentarian bête noire.

Ultimately, it is difficult to make a case for Carlson as the populist enemy of the Establishment that does not make the same case for Trump. Carlson is simply a smarter version of Trump, joined in the same goal. That the Trump project involved an alliance with wealthy interests and culminated in an authoritarian power grab tells you what you need to know about its relationship to real power.