When I wake up and check my phone in the morning, it often has a few reminders for me. Facebook tells me that I have new “memories” with friends through its “On This Day” feature — an anniversary of when I first met some rando, or an update from a long-past party. A few hours later, Google notes that it’s my mom’s birthday and it auto-tagged some photos I’m in with friends from last night. Then I get another pop-up Facebook alert for an event I’m going to that night. I can’t tell if technology is making me lose my memory, or if I now have too much of it.

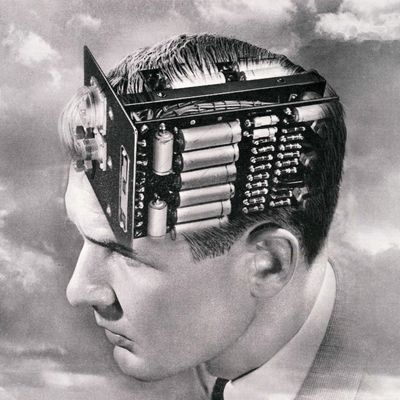

Prosthetic knowledge, as the title of a popular tech Tumblr has it, means “information that a person does not know, but can access as needed using technology.” The internet, particularly social media, has given us a place to store our memories in a way that was previously unimaginable — not only can we Google the population of a country or the location of a restaurant rather than recall it ourselves, we can also use Facebook and Twitter to chart out our social circles, not to mention our entire adult lives.

This prosthetic knowledge can be kind of scary, since we don’t actually control it. Sometimes it feels like social media has taken over our brains, orchestrating our social calendars with reminders and prodding us to recall events we might sometimes rather forget — bad breakups, or even deaths in the family. So our memories are in the clutches of a bunch of uncaring algorithms, secretly shaping our lives. Thankfully, the internet’s impact on our brains isn’t quite that terrifying.

It’s true that we have to remember less random information than generations past, but we’re more focused on remembering something else — how to retrieve the information. “When faced with difficult questions, people are primed to think about computers … when people expect to have future access to information, they have lower rates of recall of the information itself and enhanced recall instead for where to access it,” a Columbia-led study found in 2011.

In other words, while it’s not important that you memorize the population of the U.S., it is important that you know how to find it (same with your significant other’s birthday). In one study with information stored in folder systems on a computer, participants “who were told they could look back on the information didn’t remember facts, but remembered the color of the folder,” says Tracy Packiam Alloway, an independent psychologist and former director of the U.K. Center for Memory and Learning in the Lifespan.

There’s a criticism that relying on social media means “losing our ability to keep everything in mind,” Alloway says. But it’s actually the opposite — the internet “frees up brain resources” so that rather than trying to memorize information, we’re actively engaging with it. Social media strengthens our ability to filter for data that’s relevant to us, the way we’re all used to picking out the one funny or important tweet out of an endless feed.

In another study, Alloway gave a standardized test to high-school students, some whom had used Facebook for less than six months and others who had used it for years. “Teens who had been on for longer had higher working memory, better verbal skills, better vocabulary, and language as well,” she says. Rather than destroying their minds, Facebook helped them practice deciding what to pay attention to and what to forget, as we have to do even with Facebook’s curated feed. Using YouTube, however, doesn’t help kids, according to tests, because it’s too passive. “It’s not the same kind of incoming information,” Alloway says.

It’s also easy to feel like social media is just an ephemeral avalanche of information. We can’t engage with it in the same way we can, say, a printed book, or a conversation with other living humans at a café. “You no longer have those vivid memories of interaction, your memories are located within the internet,” says NYU developmental psychologist Niobe Way. “It’s a much more passive experience. What we know about memory is, the more passive it is the less likely it’s going to stick.” Yet it turns out that social media is actually strikingly easy to remember.

A 2013 experiment found that participants could remember Facebook posts from friends faster and longer than sentences from books, even without the quirks of internet language: “The difference was not due to posts containing emoticons, unique characters, or many or few words; the advantage persisted when all such posts were removed,” the report stated. What’s more, Facebook posts performed even better against the memorability of human faces. “The posts may naturally elicit social thinking and lead to stronger encoding of the posts … The relatively unfiltered and spontaneous production of one person’s mind is just the sort of thing that is readily stored in another’s mind.”

The stickiness of social-media memories can actually distort the truth, however. Social media has the power to “undermine the coherence between our real, lived lives and memories,” Dr. Richard Sherry, a founding member of the Society for Neuropsychoanalysis, told the Telegraph. Precisely because it’s easier to recall, the information we choose to store on the internet and social media has a tendency to warp our memories rather than clarify them. Even after just a few repetitions, memories can become massively distorted, another study found.

This means that all the stuff that Google or Facebook constantly reminds you of is what you’re going to actually remember, which might be the scariest part of all. Keep selectively editing those social media profiles! It’ll make you a lot happier in the future.