Did an Experimental Stem-Cell Treatment Save Gordie Howe, or Is That Just What His Family Wants to Believe?

And how much of the hockey legend belongs to a public who still wants a piece of him?

Gordie Howe Protocol

On the Sunday before last Halloween, Cathy Purnell found her father, Gordie Howe, lying on his bedroom floor in Lubbock, Texas. His eyes were closed and the right side of his mouth hung slack. When she tried to rouse him, he didn’t respond. Howe, who was 86, had suffered a stroke. He was paralyzed on his right side, could barely talk, and, once he’d returned from the hospital, needed someone to lift him from his bed to a wheelchair and back. He couldn’t remember the names of his four children — Marty, Mark, Cathy, and Murray — and over the next several weeks, his condition only grew worse. One day, Mark found him crying alone in bed. When Mark took him to get an epidural to relieve his back pain, the doctor took one look at Gordie and asked Mark if it might be better to just let his father go. On the rare occasion when Gordie managed to speak, he would sometimes tell his children that he had one last request: “Just take me out back and shoot me.”

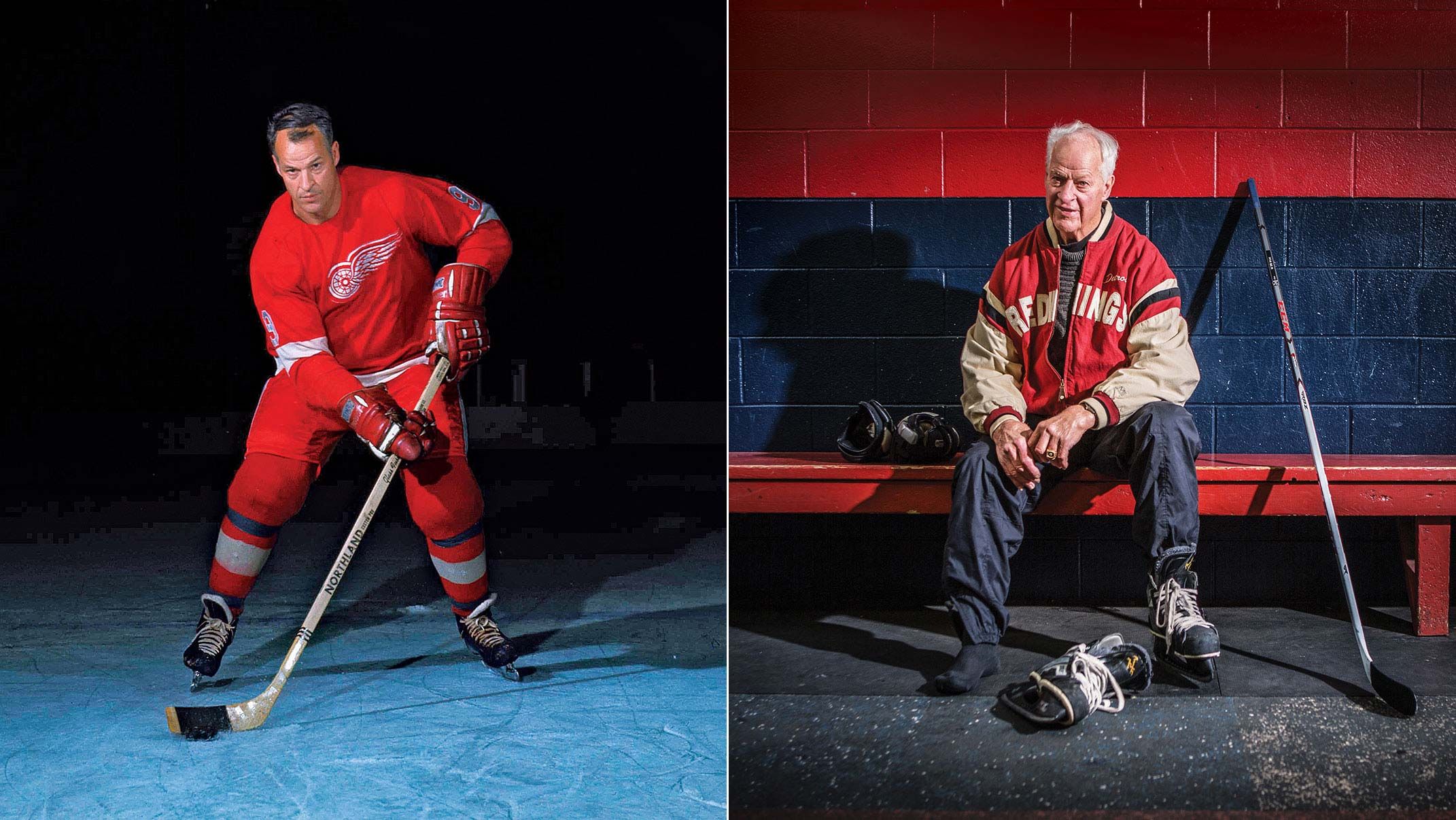

Howe, who vies with Wayne Gretzky and Bobby Orr for the title of hockey’s greatest player, had long seemed invincible. He played his first NHL game for the Detroit Red Wings in 1946, at 18, and didn’t retire for good until 1980, at 52, having scored more goals than anyone else. But over the past decade, fans had followed Howe’s slow decline from a murderer’s row of ailments — heart disease, dementia, spinal stenosis — and despite the family’s best efforts to keep it private, his stroke made the front page of the Detroit News. Keith Olbermann aired a preemptive obituary on ESPN. The family made funeral plans. Murray, his youngest son, wrote a eulogy.

But around Thanksgiving, as he began refusing to do his physical therapy — “We had never seen him quit anything,” Mark said — the family received a call from Dave McGuigan, the marketing chief at Stemedica, a stem-cell manufacturer in San Diego. McGuigan had once worked for the Red Wings and told the Howes about an experimental treatment Stemedica thought could save their father: the injection of up to 100 million neural stem cells into his spinal column, in the hope that they would migrate to his brain and help his body repair itself. Howe could improve within 24 hours, Stemedica said, and receive the treatment anytime — just not in the United States. The procedure wasn’t FDA-approved, and Howe would have to go to a clinic in Tijuana.

Medical tourism is a boom industry: The CDC estimates that 750,000 Americans each year seek medical care abroad, where it is often cheaper and doctors are willing to perform riskier procedures they can’t, or won’t, in the United States. Despite the potential hazards, the Howes considered Stemedica’s offer, and, as in many families dealing with a parent in decline, not everyone agreed on what to do. Murray, who is a radiologist, and the family optimist, looked into the idea and thought it had promise. Marty was concerned about the difficulty of transporting his immobile father to Mexico. Cathy worried that he might die on the operating table. Mark took a starker view: “If he does die, what’s the difference? He’s gonna be gone soon no matter what.”

As the family deliberated, Howe was admitted to the hospital with severe dehydration, a side effect of his unwillingness to swallow, which had cost him 30 pounds. The Tijuana discussion was tabled. When Cathy brought him home, he still had no use of his right side, and she assumed he would never walk again. But that night, she watched Gordie suddenly drag his wheelchair across the floor with his foot. It was the first time any of the Howes had seen such a spark. She sent a video to Murray and said, “You want to call them stem-cell people?”

Two days later, the Howes laid their father — “a 200-pound jellyfish,” as Marty put it — into the back of a minivan, drove him to the airport, and flew to San Diego. In the air, Gordie grew agitated and got the attention of a flight attendant, who spent ten minutes kneeling by his seat trying to understand something he wanted to tell her. Howe’s memory loss had taken hold such that he didn’t know he had suffered a stroke, why he was on a plane, or where he was going. But he remembered one thing, which he managed to whisper to the attendant: “I was a pro hockey player.”

The next morning, Marty and Murray drove with their father across the border to Clínica Santa Clarita, where Gordie bent over a table to expose his lower back so that a needle could be inserted into his spinal canal to inject the stem cells. The procedure then required Howe to lie prone for eight hours. After that deadline, around 9 p.m., Howe told Murray he needed to use the bathroom and that he intended to walk there in order to do so. Since the stroke, Murray had coaxed his father to take ten steps with a walker, but only once.

“Dad, you can’t walk,” Murray said.

“The hell I can’t,” Howe replied, according to his son, before throwing his feet over the side of the bed, standing up, and, with Murray’s support, walking for the first time in more than a month.

In Howe family lore, Gordie’s trip to the bathroom quickly took its place alongside his 801 career NHL goals, and Murray and his siblings repeated the tale in dozens of interviews as Gordie’s revival became an irresistible story for the sports pages. Back in Lubbock, Gordie returned to something resembling the normal life of an 86-year-old. He pushed the grocery cart, helped with the dishes, and could go fishing so long as one of his sons reminded him that a tug on the line meant he needed to start reeling. The family released a video of Gordie standing stationary, firing a puck, five-hole, past his 8-year-old great-grandson. Olbermann apologized for calling it early.

The Howe children had always shared their father with the public, and they now had to figure out how to share his apparent resurrection, a debate that proved just as contentious as their decision to fly him to Mexico in the first place. After Murray posted a video of Gordie watching Red Wings fans chant his name at a game, Cathy complained that he was letting the public too far into the family’s private matters, and he took it down. Both Marty and Mark had played in the NHL alongside their father, but now Murray, the doctor, was giving interviews in his hospital scrubs, endorsing his father’s place in the medical pantheon. He began referring to the stem-cell treatment as the “Gordie Howe Protocol,” and said that his hospital, in Toledo, was looking into conducting an FDA-approved study of the procedure. In one interview, Murray declared, without much of the skepticism that might be expected of a physician, that “stem cells are the most promising thing in medicine since the discovery of antibiotics.”

As the story spread, the medical community started to question just how miraculous Howe’s recovery had been. “Companies selling these products are preying on desperate and vulnerable people and exploiting their hope, much like snake-oil salesmen have done throughout most of human history,” wrote Judy Illes and Fabio Rossi, stem-cell experts at the University of British Columbia, in the Vancouver Sun. Even advocates pointed out that, though the field holds great promise, no reputable studies have shown that such a procedure should work. Gordie Howe’s body had once been used to sell hockey tickets, and now, perhaps, it was being used to sell a dubious medical treatment. Stemedica had covered the expense of Howe’s therapy, but the same care would cost anyone else $35,000.

And yet, for a child, the whys and hows of an ailing parent’s recovery hardly matter, and such questions were easily dismissed with Murray’s response to one such skeptic: “What would you do for your father?”

The first time Gordie Howe nearly died was March 28, 1950, three days shy of his 22nd birthday. In a playoff game against the Toronto Maple Leafs, Howe went hurtling toward an opponent, looking to inflict pain, but instead went crashing headfirst into the boards. The crowd sat in silence as Howe lay motionless, blood leaking from his forehead and staining the ice. At the hospital, doctors declared that he’d suffered a broken nose, shattered cheekbone, and lacerated eyeball, not to mention a concussion. Of greatest concern was the hemorrhaging inside his skull. Doctors spent 90 minutes drilling a hole above his right eye to relieve the pressure strangling his brain. The accident left Howe with a facial tic and a nickname — “Blinky” — but the latter didn’t stick: The next season, Howe led the NHL in scoring, on his way to netting so many goals, starting so many fights, and so personifying the sport’s rugged ethos that everyone just started calling him “Mr. Hockey.”

Howe grew up in Saskatoon, 250 miles north of Montana, where 4,000 people once watched him play a middle-school hockey game. When his mother went into labor, in 1928, she was alone with her children, chopping wood, so she went inside, gave birth, and cut the umbilical cord herself. Howe’s upbringing — magazines for shin guards, frozen horse droppings for pucks — laid a foundation for the ruthless style he brought to the ice. Today, a player is said to have recorded a “Gordie Howe Hat Trick” when he notches a goal, an assist, and a fight in a single game.

But the dropped gloves came at a cost. When he was 49, Howe spent breaks on the bench with his left hand in a bucket of warm water, to combat arthritis, and his right hand in a bucket of ice, to heal yet another broken bone. By the end of his career, whenever a new doctor handed him a chart and asked him to mark where he’d been injured, he simply drew a line from top to bottom and wrote, “All of the above.”

All of the above included his head, and his children believe that their father’s hockey years had an effect on his retirement. “You play 30 years at that level without a helmet and things are going to happen,” Murray says. Doctors have posthumously diagnosed at least four NHL players with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the brain disease plaguing the NFL. Howe didn’t talk much about his brain in his memoir, but his children, who lived with the effects, devoted part of their epilogue to it: “We cherish our time with Gordie all the more these past few years as it has become clear he has been dealing with cognitive impairment, a form of dementia.”

It was not the first time they had been required to guide a parent through the vagaries of cognitive decline. In 2000, Howe’s wife of five decades, Colleen — “Mrs. Hockey,” as she became known — was diagnosed with Pick’s disease, a particularly rare and insidious form of dementia. Mark described her eyes as soulless, like a shark’s, and said that her illness “was taking the life out of two people.” In a span of two years during his wife’s illness, Howe suffered chest pains and dizzy spells and went to the hospital ten different times.

Colleen died in 2009. At the memorial, Howe’s legs nearly gave out when he tried to stand. After Colleen’s death, he would occasionally pick up a team photo from the ’40s and move his finger down the row of players, repeating, “He’s dead. He’s dead. He’s dead.” When he got to himself, he said, “I might as well be.”

Lubbock is a cotton town in a part of West Texas so flat it appears to have been smoothed over by a Zamboni, which is unlikely because it is also, by one local estimate, the largest city in America without an ice rink. “The closest one I know of is in Dallas, and it’s in a mall,” Misty Matthews, a Lubbock native, said one day last month at Eddie’s Barbeque, where she was digging into a Frito pie along with Cathy and Marty Howe. “But I actually watched a hockey game recently and realized NASCAR’s just like hockey. They just get outta the cars to fight.” After spending several years rotating among the homes of his four children, Howe moved to Lubbock last August, before the stroke, to live full time with Cathy, who had relocated there a few years earlier. The members of the Matthews clan, who all go by nicknames — Corky, Buff, Li’l Fella, Scooter, and Scrub Brush — had become a surrogate family, running errands for the Howes and serving as muscle whenever Marty, Mark, and Murray weren’t in town, despite the fact that none of the Matthewses had ever heard of Mr. Hockey.

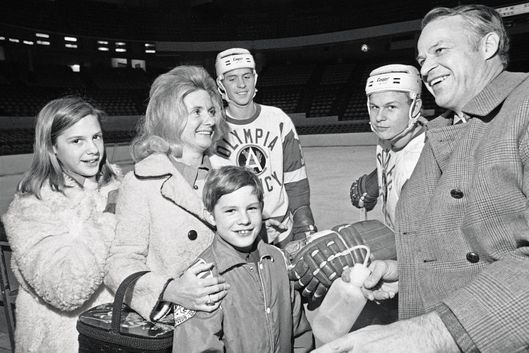

In certain northern parts of the U.S., and all of Canada, however, the Howes are royalty — akin to the Mannings of football. Gordie is perhaps the best hockey player of all time, Mark is in the NHL Hall of Fame, and Marty played professionally for 14 years. In the ’70s, they all suited up for the same team, the Houston Aeros, like something out of a sappy sports movie. (In 2013, the Hallmark Channel made one.) Even though Mark, who is younger than Marty, quickly became the better player, there wasn’t much jealousy between them. “We spent most of our time talking about dealing with being Gordie Howe’s kids,” as Mark put it in his memoir, which he chose to call Gordie Howe’s Son: A Hall of Fame Life in the Shadow of Mr. Hockey. During games, fans would often yell at the boys, “You’re not as good as your father,” to which Marty learned to respond, “Who is?”

In 1975, Colleen Howe published a memoir called My Three Hockey Players, a title that excluded Murray, her youngest, who recently submitted a manuscript of his own about being the only Howe male to never play professional hockey. “He played because he thought it was expected of a Howe,” Mark said of Murray, who is smaller than his brothers — Gordie used to call him “the little guy” — and was cut from his college hockey team. “I thought I was going to the NHL, and the scouts didn’t tell me otherwise,” Murray said wryly. “I wish they had put me out of my misery.”

Cathy never felt the same pressure. “Because I was the only girl, my direction was easy,” she said. “It was whatever fork I decided.” Still, she’d been bitter when the family left Detroit for Texas during her high-school years so Marty and Mark could join their dad on the Aeros. As soon as she could, she returned to Michigan and married her high-school sweetheart.

In their father’s post-stroke life, each of the Howe children had taken on a particular role. Mark, a scout for the Red Wings, was the family’s connection to the hockey world, while Marty continued to run the business of being Gordie Howe, officially known as Power Play International Inc. In recent years, Gordie had made as many as 70 annual appearances, though the number had dwindled as his health declined, and in February, when Howe shuffled onstage at a charity dinner in Saskatoon, Marty announced that the family expected it would be his last time in public.

Because Cathy rarely travels — she owns and runs Texas Trailer Corral — the burden of caring for their father day-to-day had largely fallen to her. “I get to see my brothers all the time,” she said of their frequent visits. “Which is fun, so long as the taskmaster doesn’t push Dad too hard.” She nodded at Murray.

“I do much more physical therapy than he gets normally,” Murray said with a shrug.

“I love my little brother, but sometimes I text Marty and Mark and say, ‘What color coffin do you want?’ ” Cathy said.

As the family’s resident doctor, Murray, who is now in better physical shape than both of his professional-athlete brothers (he runs marathons), had become his father’s primary medical decision-maker, talking with doctors and coordinating his therapy sessions. Still, when Stemedica came calling, he hadn’t considered stem cells as an option, with good reason: There is no such treatment that has been established as a standard of care for stroke. But the company presented the Howes with several options. First, it was sponsoring an FDA-approved trial in Arizona and California to see what effect intravenous delivery of stem cells derived from bone marrow might have on stroke victims. However, because stroke patients often improve on their own within six months, Howe would not be eligible for another five months. The family wasn’t sure he had another five weeks.

The second option, Stemedica said, was even more promising: a dual treatment involving both the bone-marrow cells and neural stem cells, derived from fetal tissue. This treatment could happen more or less immediately, but would require traveling to Mexico or Kazakhstan. The former Soviet Union is the Silicon Valley of experimental stem-cell treatments, and Stemedica had been founded by two brothers after their sister-in-law, Arlene, went to Russia to receive stem-cell treatment for a spinal-cord injury. Several years after her treatment, a local newspaper reported that the stem cells had not repaired her spinal cord, and that Arlene credited her progress “to God.”

Last year, Stemedica began selling its stem cells to a clinic in Tijuana that works with Novastem, whose CEO, Rafael Carrillo, is a civil engineer who told me his family’s core business is real estate. Novastem provides clients with a “concierge service” to “supply luxury, personalized, private transportation locally or to/from San Diego” and accepts payment via cash or wire transfer. Clinical trials in the U.S. rarely require patients to pay for the privilege of being experimented on. (As explanation, Carillo says, “we’re not a Pfizer.”) Novastem had previously offered stem-cell treatments for everything from osteoarthritis to erectile dysfunction, but Howe would be the clinic’s first stroke patient.

By the account of every Howe child and several therapists who saw him before and after, Gordie had gone to Tijuana with one foot in the grave and returned shoveling dirt back in. But many stem-cell and stroke experts questioned the assertion that the stem cells had led to his recovery. The speed with which the treatment supposedly went to work on Howe’s brain — a matter of hours, rather than weeks or months — seemed especially improbable. “It’s just as likely that it was angels as stem cells,” said Jeanne Loring, a researcher at Scripps Research Institute developing stem-cell treatments for Parkinson’s. There are a number of trials in the U.S. looking at whether stem cells might be used to treat stroke, but most are still at the animal stage. In April, Athersys, a Stemedica competitor, published the results of an FDA-approved human study into a bone-marrow treatment similar to the one Howe received: It found that, when compared to a placebo, patients showed no improvement.

But if not stem cells, then what? Proper hydration and care, which Howe got during his hospitalization for dehydration, might have jump-started his recovery, as could a placebo effect from having a needle stuck in his spine. In the first six months after a stroke, victims often experience unexplained recovery of the kind that Cathy had seen when her father walked his wheelchair across the room or that Murray had witnessed in Tijuana.

Stemedica said it paid for the procedure out of affection for Gordie Howe, but doing so also provided a clear publicity bump for the company. (Both companies deny any quid pro quo.) After his treatment was announced, the Howes started getting three or four calls a day from people interested in the therapy, including the family of Bart Starr, the Hall of Fame quarterback, who had recently suffered a stroke. “A lot of the same principles in using celebrities that you use in sports marketing were possible to apply to cause-related marketing,” Dave McGuigan, the Stemedica executive who worked with the Red Wings, told me. Stemedica had previously publicized its involvement in the treatment of John Brodie, a former NFL quarterback, for a stroke, and after Howe’s treatment, both Stemedica’s CEO and Murray went on Olbermann’s show. Speaking generally, because of Stemedica’s reputation for threatening legal action, Larry Goldstein, a stem-cell researcher at UC San Diego, said, “When you have one patient of a clinical trial of a treatment, it is irresponsible in the extreme to go out saying, ‘We know this works.’ ”

Still, some stem-cell advocates argue that American regulations deny patients promising if unproven treatments available in other countries. (A number of athletes, including Peyton Manning and the Mets’ Bartolo Colon, have gone abroad for stem-cell treatments to help speed recovery from injuries.) McGuigan said Stemedica hopes to use the results from the studies abroad to get FDA approval for a trial in the U.S. “Just because it’s Mexico or Kazakhstan doesn’t mean they don’t have regulatory overseers who take their jobs very seriously,” he said. But for this trial, Novastem was depending on the Howe family to collect data on their father. “No ethics review board in the U.S. would say, ‘Give this extraordinarily complicated therapy and have the patient just call in to say, Here’s how I’m doing,’ ” Corey Cutler, a stem-cell researcher at Harvard Medical School, told me.

Researchers remain excited about stem cells as a potential treatment for stroke, but stress that years of investigation are still needed, and many felt it was irresponsible for the Howes — especially Murray, as a physician — to promote such unqualified enthusiasm for an experimental and expensive procedure. “I feel sorry for anyone who finds this miracle ‘troubling,’ ” Murray wrote in a statement to the San Diego Union-Tribune, which had asked questions about the treatment. But none of the Howes is willing to consider other causes for their father’s recovery: They have since become investors in Stemedica and plan to send Gordie back to Tijuana for another injection on June 8. Murray seemed especially excited by the prospect of his father becoming a major figure in his profession. “With all the sacrifices he made for hockey,” Murray said, “he may end up being most remembered as patient No. 1 for the Gordie Howe Protocol.”

Becoming a medical icon is hard work. One afternoon in late March, three months after his trip to Tijuana, Howe walked across the parking lot of a rehab center in Lubbock wearing cargo pants and a polo shirt with the Texas Tech University logo. His hockey career left him with elbows the size of cauliflower heads — Murray said his father’s X-rays look like nothing he’s ever seen — and his nose, which he broke 14 times, has a permanent indentation. He insists on greeting visitors standing up, which is a struggle, and speaks in a barely audible whisper.

Gordie was being trailed in the parking lot by a camera, a boom mike, and Murray, who, in addition to managing his father’s medical care, had become the family’s chief spokesperson. Since the event in Saskatoon, Marty had cut all appearances from his father’s schedule, but Murray, after debating the idea with his siblings, had agreed to invite Avis Favaro, a Canadian medical reporter for CTV News, to film a documentary on Gordie’s recovery. “People have really demanded the information from us,” Mark said. Murray had taken it upon himself to offer correctives whenever his siblings misspoke about their father’s medical condition, though his reports were often overflowing with positive adjectives that didn’t always match the medical reality. “Murray’s always like, ‘Dad’s doing wonderfully!’ ” Mark said. “And relatively speaking, he is, but when Marty’s there, I get what’s actually going on.”

What was going on was that Howe had good days, when he might walk around the block, and others when he needed three or four naps to get by. Howe had only recently started outpatient therapy — even Mr. Hockey is at his insurance provider’s whim — and the therapist began putting him through a series of workouts. “You ready to show off today?” she asked Howe as the cameras rolled. One reason the Howes say they tried the stem-cell treatment, rather than heed the doctor’s advice to let their father drift into the night, is that Gordie’s personality — unlike Colleen’s — had largely remained intact despite his dementia. In rehab, he successfully bounced a tennis ball from one hand to the other, but when he struggled to lift a cylinder of PVC pipe to his shoulder, he took the pipe in both hands like a baseball bat and took cuts as Murray tossed a tennis ball his way. His swing was more of a bunt, but his batting average was surprisingly high. “Who’s cooking the fastball?” he whispered.

While the camera crew asked Murray to keep giving batting practice so they could shoot from a different angle, Marty stood in a corner, behind the cameras. Cathy had declined to be interviewed and declared her house off-limits to the crew, while Marty had agreed to go along but had little interest in being on-camera. When Favaro’s producer asked Marty to stand alongside Murray, next to their father, he replied, “This is Murray’s time.”

“Well, it just helps,” the producer said.

“For the story?” Marty asked with faux indignation, before walking over to stand in the frame. “Where’s my agent?”

After half an hour, another therapist walked Gordie into a different room and coaxed him through an obstacle course. The CTV cameraman, wearing a pair of knee pads, danced around the room as Murray walked his father around the room.

“Do you wanna give him a bit of a rest?” Favaro asked as Gordie took a break on a bench.

“He’ll be okay,” Murray said. “He’s used to 32 years of ‘Whatever the coach tells you to do, you do.’ He likes it.”

Gordie didn’t look like he liked it. Toward the end of the session, while standing on a balance block, he needed Marty to wipe his nose with a Kleenex while the CTV cameras kept rolling inches from Gordie’s face. When the workout ended, the film crew asked Gordie to sit with a neurologist they had flown in from California to assess him. “I just had some questions for you,” the neurologist said, pulling up a chair next to Gordie in the rehab center’s lobby. When the neurologist asked him his age, he got no response. They tried walking down the hall, before Gordie aborted the plan and sat back down. The neurologist tried a different tack. “Apart from Gordie Howe, who do you think is the greatest hockey player who ever lived?”

“I don’t know,” Gordie whispered.

Murray jumped in to urge him along. “Dad, if you were gonna pick between Bobby Orr, Bobby Hull, or Wayne Gretzky, who would you choose?” Murray said. “Or Mark Howe?” Gordie smiled. “I’d pick Mark too,” Murray said. “Don’t tell Marty.”

Marty had, by this point, left the room in a huff. Watching the decline of a parent is difficult for anyone, but letting the world tag along is even more complicated, and Marty had initially asked that his father not be interviewed on-camera. “His brother is super-angry,” the CTV producer whispered to Favaro, who left the room to talk to Marty. Murray maintained a smile during the questioning but showed some frustration when the neurologist asked what Gordie thought of his experience in Tijuana. “He doesn’t remember what happened five minutes ago,” Murray said. As other patients walked by, the producer sheepishly asked if they could move the session to a private room. Marty paced outside the rehab center. “That sort of stuff bothers me,” he said later. “I’m just very protective of my dad.”

Several days after the cameras left, Gordie celebrated his 87th birthday. He ate barbecue and watched a Red Wings game, during which the team handed out Gordie Howe bobbleheads. Mark still hoped to bring his father to Detroit for one last Jumbotron appearance, but Gordie had hit a rough patch. The family decided to move his therapy back home. “The last session, he just didn’t want to do anything,” Marty said. “He’s not gonna live to 104 anyway, so we thought, Let him enjoy himself.”

Even Murray, the eternal optimist, was uncertain about the future. “It may be that his warranty is just expiring and age is finally catching up with him,” he told me in May, a day after the Canadian prime minister announced that a proposed bridge between Windsor, Ontario, and Detroit would be named the Gordie Howe International Bridge. (The developers seemed to recognize that Gordie Howe’s name could perhaps be used to sell a bridge, too.) Later this summer, after he returns to Tijuana for his second treatment, the Howes are planning to move Gordie to Toledo, so he can live with Murray. Despite the spats over how best to share their father’s final act and the pressure of being at the heart of a medical controversy, each of the siblings agreed that the extra months with their father had been worth it. “It might not be a miracle for everybody,” Cathy said. “But for this family, it is.”

None of the third generation of Howes has displayed the hockey prowess of their parents, let alone their grandfather, but Murray’s youngest son, Sean — he has another named Gordie — is a sophomore at Juilliard, studying dance. Murray refers to his son, who hopes to one day join a European dance company, as “the Gordie Howe of dance.” Gordie can no longer travel to see Sean perform, but for all the fog clouding his brain, there is still an occasional fluidity to his ex-athlete’s frame — a reminder that, behind the medical and family drama, surely no one had gotten more joy out of his recovery than Gordie himself. At one point during rehab, as his therapist tried to walk him from one seat to another, Gordie grabbed both of her hands.

“Are we gonna dance?” she asked.

After a moment’s pause, Howe lifted her right hand and twirled her around, swinging his arm above her head before wrapping her in an embrace from behind. “You’re gonna make me blush!” she said. There was no second step, but one was enough.

*This article appears in the June 1, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.