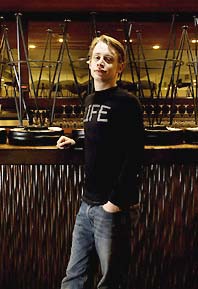

To be a child star is to be a permanent spectacle, a one-man freak show, an eternal curiosity. Macaulay Culkin has been in only two films in the past twelve years, and yet as we walk to our table for lunch at Coffee Shop, people whisper, gawk, and, in one unfortunate instance, forget how to properly sip liquid through a straw. It doesn’t help that, at 25, he still looks startlingly like he did sixteen years ago in Home Alone, when he slapped aftershave on his pale cheeks, gave a bug-eyed shriek, and became a pop-cultural phenomenon before he understood the concept of pop culture. “To a lot of people, I still am that kid,” he acknowledges. “It’s a blessing and a curse. I can go to any restaurant without a reservation, but while I’m there, everyone’s gonna be staring.”

Child actors are supposed to play two roles. As kids, they embody a mythically wholesome version of childhood; as adults, they are expected to personify a more ominous stereotype, living in a state of suspended implosion. “Yeah, it’s funny,” says Culkin. “A lot of people meet me and they’re like, Why aren’t you crazy?” As if to add to the confusion, he has now produced what he aptly deems “a strange, weird little book” called Junior, a quasi-fictional chronicle of a former child star who may or may not be borderline certifiable. “Yes, it’s me,” says Culkin, “but no, it isn’t, you know?”

In person he is quick-witted and chatty, affable but distant, someone who learned to interact through professional exchanges, not personal ones. He manages to be simultaneously oblique and revealing, constantly checking the tape recorder to make sure it’s picking up everything he says. He tells me repeatedly that he leads a “simple, simple life,” spending his free time walking the dog, feeding the fish, cleaning the house, and cooking for his girlfriend, Mila Kunis, who just ended her run on That 70’s Show. As for his own career, he isn’t retired, as some have surmised, though he jokingly refers to himself as “not exactly the hardest-working actor.”

An understandable position, given his past. Just glossing over Culkin’s coming-of-age is psychologically exhausting: Raised with six siblings in a one-bedroom on Second Avenue and 94th Street, he started scoring choice roles at age 8 and was a millionaire by 10, but his rapid ascent seemed less adorable and precocious the more people learned about his home life. His father, Kit, notoriously ruled the family—“his kingdom,” says Culkin—by humiliation and physical abuse, eventually leaving the household in 1995. That’s when his mother, Patricia, filed a custody suit, igniting a bitter public battle with Kit, and Culkin had his parents legally blocked from controlling his $17 million fortune, a move that forever estranged him from his father, who today Culkin “thinks” lives in Arizona. “I learned how to read court papers at 14,” he says, inadvertently quoting his alter ego, Junior. At 17, Culkin married actress Rachel Miner; by 20, he was divorced. When he was arrested a little more than a year ago for possession of marijuana, he was most frustrated to be perceived as conforming to type. “You know, I am a former child actor,” he says with a sarcastic chuckle. “I’m supposed to be a lot more fucked up than I am. I took a certain amount of pride that I wasn’t that cliché, so it was, like, Oh, great, I gave a lot of people exactly what they wanted.”

Novels written by celebrities tend to be grating, solipsistic affairs. Given a choice between Ethan Hawke’s literary fiction and the veiled memoirs of glittering train wrecks like Nicole Richie, most sane people would choose television. When I heard that Culkin was now a novelist, I rolled my eyes along with everyone else, a reaction I had to suppress repeating when he prefaced our chat by announcing, “The funny thing is, I’m not really a big reader, not a big fan of books in the first place.” But Junior turns out to be oddly, unwittingly … compelling. A postmodern mishmash filled with drawings, epistolary fragments, personal manifestos, and public diatribes, the book is best appreciated as a piece of conceptual art rather than a legitimate novel. Tear out the pages, staple them to a wall, and you’d have a deconstructionist installation, an accidental dissertation on the crippling self-consciousness brought on by early fame. Child Actor: Fall and Rise.

“In a perfect world, my name wouldn’t even be on it,” says Culkin, who prefers to think of the book as a meta-artifact of celebrity. “It came from the idea of everyone wanting me to write a memoir. I play with that a little bit, the idea of naming names, kind of teasing people, you know?” Early reviews of the book have not been kind—“self-indulgently infantile,” scolded Publishers Weekly—but he isn’t surprised. “I’m not expecting the American literary community to welcome me with open arms,” he says. “To them I’m just some schmuck kid who wrote some book.” If Junior has a clear theme, it’s coping with fame, a subject that brings out Culkin’s caustic side. “I really disassociated myself from ‘Macaulay Culkin’ mentally,” he says. “Like, if someone actually calls out that name on the street, I don’t turn my head. Literally. When I was 14 and I quit, I said I’m never doing that again—say whatever you want about me. That I’m crazy, that I’m an alcoholic. Call me a drug addict. I don’t give a shit anymore. That’s not me anymore. That’s for you. It’s yours. Go ahead, have fun.”

For all its tangents, the book continually circles back to a single subject: Junior’s relationship with his father, a figure who has much in common with Kit Culkin. “I think there’s two different fathers that I have,” says Culkin. “I have my father, and I have the one in my head. The real one is gone and should be gone. But I think I was looking to put the one in my head to rest.” There is not a flicker of emotion as he speaks; it’s as if he’s describing a character in a film rather than the man responsible for his existence and career. “He would black out all the terrible things that he did, and that hurt me more, because he’d go to bed at night thinking he was a good person. People do bad things in their lives. And those sort of things are forgivable. That’s half the point of having confession in church—you need to be able to fess up to what you’ve done. He just couldn’t. It was some kind of mechanism in him or some kind of craziness.” Culkin says he feels a bit guilty over the book, but in a way, he’s been working on it since childhood. “I knew from a very early age that I better take notes on him,” he says of his father. “Notes on how not to be, notes on how I don’t want to be when I grow up.”

In a sense, Culkin has aged in reverse.

“I have a lot of growing up to do,” he tells me at one point, before correcting himself, “or a lot of growing down. I think that’s probably more appropriate.” The stuff of his childhood—work, pressure, fame, wealth, marriage, divorce—reads like a checklist of adult milestones. Meanwhile, at an age when his peers are drifting into adulthood, he is a self-sufficient slacker enjoying a latent adolescence, not worrying about money or work or the future. Even the book isn’t a calculated career move so much as a lark. As he puts it, “Maybe now that I’m older, given my freedom, instead of cutting shapes out of construction paper, I’ve been making a little book.”

The following night, Culkin invites me to pick him up at his downtown loft—a nondescript building, no doorman—to grab a beer and play some pool. Walking over to Soho Billiards, he lights a Parliament and talks about the rather unusual dynamics of his family. Since gaining control of his finances, Culkin has played the role of reluctant father, subsidizing the lives of his siblings as well as his mother. “I have a family to support,” he says later, racking the balls. “Essentially it’s like an allowance. It’s hard. You don’t want to feel like you’re controlling, like you’re in charge. There’s always a little more money around Christmastime—large family, lots of presents.”

“It’s the worst possible thing I could have done for myself. Now I have to stand by it. I can’t just throw it out there and act like I’m ashamed of it.”

When Culkin’s younger brother Kieran learned of the book, he was concerned that it would be used to fan flames that in recent years have finally stopped smoldering. “They were the right fears,” Culkin concedes, mentioning recent tabloid headlines (Daily News: MACAULAY WRITES A SCARY FAMILY SAGA; Post: TOME ALONE—INSIDE MACAULAY CULKIN’S MADMAN DIARY). “Yeah, it’s the worst possible thing I could have done for myself,” he says flippantly. “Now I have to stand by it. I can’t just throw it out there and act like I’m ashamed of it.” He mulls this over. “I’m willing to face whatever comes with this, from critics, people trying to make it more sensational than it is. This is not a sensational book. There’s no Michael Jackson references at all, so get that out of your head right now.”

That’s easier said than done, given that it was less than a year ago that Culkin testified for the defense during the pop star’s molestation trial. “You know, I didn’t want to get involved with the whole thing,” he says. “It was a big, fat mess. I almost wanted to say to him, ‘You should have known better, just to even have those kind of people in your life.’ ” He thinks for a moment and continues. “I don’t know how it happened, but somehow I’ve become the resident Michael Jackson expert. We’re close, he’s a good friend of mine, we definitely have a connection that most people don’t have, but he’s a friend that I talk to once a year.” When they talk, Culkin always encourages Jackson to get back to music. “You know, call up the Roots, call up the Beastie Boys, call up Björk.” The last time they spoke was a few months after the trial: “He sounded better …” He trails off, distracted. “One of the things that I always thought is that I could have turned out that way. I’m a fairly sheltered person, but I could have just put up a fortress around myself, bought a big chunk of land somewhere, and said, ‘Fuck all y’all!’ But I made a decision when I was 14 that I was going to live life, where I think he made the opposite decision. It’s a cool little world that he has, but at the same time, it’s become a little more distant from reality.”

Of course, being in the real world isn’t always easy. As we play pool, a woman approaches, staring at him unapologetically.

“Um, I think you’re staring at me,” Culkin finally says, causing the woman to snap out of her trance.

“Oh, uh, is that Macaulay … ?”

“No, only on my good days.”As she vanishes, Culkin laughs. “As I’ve gotten older,” he says, “I’ve realized that when it comes to things like that, people are acting out of character.” Usually, when he points out their gawking, they apologize and go on their way. Not in this case. A few minutes later the woman is back.

“I didn’t mean to scare you!” she snipes. “And don’t worry, you’re not that cute!”Culkin shrugs. “I think she just misheard me.”

It’s the sort of moment—as crushing as it is common—that provides a window into why a child star might, say, grow up to write a schizophrenic pseudo-novel. But Culkin has never been one for self-pity, and over the past five years, he has learned to enjoy himself. “I had some good times,” he says with a mischievous grin. “I was single, a divorcé. It’s not like I never went to clubs and bars and flirted with every waitress in New York City.” After a prolonged period of standard-issue early-twenties indulgence, he issued a personal edict: “I decided to be abstinent or asexual or whatever. I made a vow, yeah.” It was then that he met Kunis, whom he speaks of fawningly, finding a way to reference her in every other sentence. Though the two aren’t engaged, they often joke that they’ll end up having kids before they get married, a fittingly accelerated version of domesticity. “Being promiscuous is only fun for so long,” he says. “I decided that’s not who I am. I’m not going to end up like Scott Baio, you know?”

(1.) November 16, 1990: Home Alone released. The film will gross more than $285 million in the U.S. Says L.A. Times critic Peter Rainer, “Culkin has the kind of crack comic timing that’s missing in many an adult star.”

(2.) November 14, 1991: Michael Jackson’s “Black or White” video—co-starring Culkin—comes out. Jackson will later name Culkin godfather of his son, Prince Michael Jr.

(3.) 1997: Considered for the Leonardo DiCaprio role in Titanic.

(4.) June 21, 1998: Culkin’s child-bride-and-groom wedding. He and Rachel Miner also appear in a Sonic Youth video—directed by Harmony Korine.

(5.) October 18, 2000: Culkin resumes his acting career in a well-reviewed West End production of Madame Melville. In 2001, he reprises the role Off Broadway—the last time he appears onstage.

(6.) September 5, 2003: Party Monster released. Culkin plays club kid Michael Alig. Says A. O. Scott of the New York Times: Culkin’s “performance is earnest and brave, but also mannered when it should be un-self-conscious.”

(7.) September 17, 2004: After Culkin’s arrest for pot possession, Dennis Miller cracks, “Culkin’s publicist would not comment, because she could not remember who he was.”

Junior

By Macaulay Culkin. Miramax Books.

256 pages.