Walk around Chelsea these days and you can practically hear money buzzing in the air. Powerhouse galleries such as Matthew Marks and PaceWildenstein have extended their empires with extra showrooms. Younger guns like Leo Koenig and Casey Kaplan are graduating into grander spaces. And almost every weekend, some former gallery director is going into business for himself. It’s not just Chelsea. The whole contemporary-art market has shifted into overdrive. Playing to today’s competitive collectors, the Armory Show’s opening gala earlier this month offered three-tiered access: $1,000 to enter the art fair at five o’clock, $500 a half-hour later, and $250 for seven. But by five, the booths of the hot dealers had already been besieged by dozens of collectors and art consultants, invited in at noon by their clients; many works by sought-after artists were either sold out or held on reserve (some on “double reserve”).

Likewise, during last year’s auctions, the Postwar and Contemporary sales started to truly rival the historically dominant Impressionism and Modern categories. Granted, much of that dollar volume is driven by dependable heavy hitters such as Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and Willem de Kooning. But the younger end of the spectrum has even more momentum. Last October, for example, Christie’s capitalized on the Frieze Art Fair’s bringing international collectors to London to create a bona fide contemporary-art event. Two paintings, by Tim Eitel and Matthias Weischer of Germany’s “Leipzig School,” created a presale sensation. You could have bought such works for as little as $4,000 a few years back, before the Leipzig School hype started building, and neither artist had ever come to auction before the Frieze fair. There was some surprise when the Eitel sold at $212,000, three times the high estimate. But the stunner was Weischer. Estimated at $31,000 to $38,000, his painting soared to $370,000, instantly making it shorthand for everything overblown in the current market.

Encouraged by such rocket-fueled price increases, competitive collectors and dealers now scour both exotic places (Poland and China are current favorites) and local art schools for new names; in January, veteran Upper East Side dealer Jack Tilton’s show of students cherry-picked from the M.F.A. studios at Yale, Columbia, and Hunter sold strongly, despite the aggressive pricing for what was by definition still student work.

To second-generation dealer Marc Glimcher, president of PaceWildenstein gallery, the climate seems all too familiar. “Like the rest of society, the art market has cycles,” he explains. “The art market comes to the fore when there’s a lot of discretionary spending. Collectors are competing with each other. The prices of art accelerate. The age of the most expensive artists drops. There’s a great flowering. Schadenfreude starts building up. And then it crumbles erratically.”Such public pessimism is rare among dealers. Because if art itself is built on the image, the idea, and the object, the art business hinges on words—the spoken and written seductions that persuade buyers to pay ever-higher sums. Some words are spoken only in the back room of the gallery, where commerce is quarantined to keep it from sullying the art out front. Here are three, in order of increasing nastiness: Correction. Contraction. Crash.

You won’t see them, of course, in most coverage of the contemporary-art market. Instead, dealers recite a market mantra: Business is strong, driven by the globalization of the market. The New Economy’s collapse and September 11 created only a comparative hiccup in sales. Art has become a luxury good, coveted by the surging crowd of new wealth in search of an identity for itself. But in the back room, the thinking is not always so optimistic. Even Zach Feuer, among the star dealers of his generation at age 27, has prepared for the worst. Despite his success, Feuer runs harsh projections before any capital expenditure. “I’m checking, How do things look if sales drop 50 percent? ” he explains. “How about if they drop 80 percent?’”

In the art world, there’s a clear delineation between those who experienced the last crash, in the early nineties, and those who didn’t. “This market is fueled by collectors who have never been through a correction,” says art adviser Darlene Lutz, active since the eighties. “The generations who did are watching this with disbelief. It’s like teenagers who have unprotected sex thinking they’ll never get pregnant. And then, whoops … look what happened!”

Yet the history of art-market crashes is no more a secret than the basics of sexual contraception. Even a casual student of art-world history can recite the early-nineties fall of Soho: the paintings by art stars Julian Schnabel, Sandro Chia, and Enzo Cucchi turning unsellable; the legions of posh galleries shuttering their doors; the general sense of despair and gloom settling over the entire neighborhood. In 1993, the New York Times writer N. R. Kleinfield tested the desperation of Soho dealers. Haggling like a man buying a used car, Kleinfield consistently extracted 20 percent reductions, the discount level reserved today for major collectors and museums. At Leo Castelli, he was offered what had been only a year earlier a $400,000 Lichtenstein sculpture for $270,000.

Not surprisingly, few people want to imagine such calamities roiling Chelsea. “For the last 100 years, contemporary art has always been overpriced by comparison to older works, but there’s no guarantee that if you buy something for $200,000 it will be worth anything in fifteen years,” says Daniella Luxembourg, the former auction-house leader who in 2004 founded Geneva-based ArtVest, an investment firm specializing in art. “Everyone assumes the market will continue. And then when it stops, they will all be quite astounded. Later, everyone will say, ‘I said it couldn’t last!’ ”

What you hear most these days, of course, are art-world sages saying that it will last, positing that this time around it’s a long boom, not a massive bubble. Generally, such pronouncements are underpinned by a litany of logical-sounding reasons. They go something like this:

Crash-Proof-Market Theory No. 1

The Expanded Art World

All crash-proof-market notions hinge to some degree upon a single fact: The art world is bigger than ever. That’s unquestionable. Depending on which metric you use, the global market is up to twenty times as large as it was in 1990. “Two years ago, all the dealers I know were planning around a contraction,” says one market-making American collector, who requested anonymity. “Now they say, ‘The market’s bigger, it won’t happen.’ And it is true there’s a new class of people buying art. Maybe it’s a major economic shift, like the postwar period, when America stole the art world from Paris. But when people say a crash can’t happen again because of that shift, I think of the New Economy in 1999.”

The analogy is not that far-fetched: Just as start-ups commanded valuations disproportionate to their bottom lines, hot young artists can rapidly reach the same price levels as mid-career artists with proven track records. “Today’s art market is by and large misinformed,” says veteran adviser Thea Westreich. “People are buying in packs and syndicates, running through fairs and evaluating work, which is a sure way to go wrong. They’re using their ears, not their eyes, to select works, buying based on market trends rather than art-historical standards.”

When I run the argument of a broader market’s being inherently more stable by Los Angeles media executive Dean Valentine, a major contemporary-art collector, he goes momentarily speechless. “I see zero economic truth to the notion that rapidly expanding markets are more stable,” he says. “What you have now is more buyers overpaying and creating misaligned values.”

Crash-Oroof-Market Theory No. 2

The Art World’s Gone Global

Traditionally, major contemporary-art collectors have come from Western Europe and the United States. Now they come from all over, like Brazil (metals magnate Bernardo Paz), Mexico (juice heir Eugenio López), and South Korea (retailer C I Kim). In the trade, there’s constant debate about where the next big collectors will emerge—Russia and China, yes, but also India and various Arab emirates.

Sotheby’s contemporary-art head Tobias Meyer said recently inThe New Yorker that such buyers mean the art market’s only begun to rise. History is portentous here: “The secret is that this market is international,” Christie’s chairman John Floyd told Newsweek in 1988. “If the dollar is down, the yen and deutschmark are up.” Less than two years later, young lions like Schnabel and past masters such as Clyfford Still alike were going unsold at auction. And though the art world has definitely continued to globalize since then, this does not necessarily connote true stability. It’s not yet clear how deep the market is in these areas. Will there be enough new collectors of contemporary art who keep buying work once their walls are filled, then go on to fill up warehouses and create private museums? “If the European or American art market softened now, China, Japan, Russia, and the others could never take up the slack,” says Anders Petterson, a former bond trader whose London ArtTactic firm analyzes the art market.

Crash-Proof-Market Theory No. 3

Art Is the New Asset Class

Over the past few years, a flurry of articles identified art as a component in every savvy investor’s portfolio. Figuring prominently in many of these stories has been the research of New York University economists Michael Moses and Jianping Mei. Using the Case-Shiller methodology originally developed for understanding real-estate markets, the professors tracked artworks that sold originally at auction in New York. They found art regularly showed returns somewhat below those of the S&P 500 but significantly above any class of bonds. Over much of the last half-century, the art they tracked was about on par with the S&P 500.

Published by The American Economic Review in 2002, the study caught fire. “It’s been a blast,” says Moses. “Prior to this study, all we had were war stories, but this study put art on the same footing as other financial assets. It’s a trillion-dollar asset class that in many ways works a hell of a lot like real estate.” Moses recently retired from teaching to focus on Beautiful Asset Advisors, a company aimed at monetizing the Mei-Moses research data.

The pair have hardly been without their critics, who assail them for not counting in their data work that fails to sell or “sunk costs” such as insurance and shipping, not to mention the onerous commissions exacted by auction houses. But most of the criticism stems from something beyond their control: the sloppy fashion in which both journalists and the art world deploy any numbers that fall into their hands, in this case using the Mei-Moses index as proof that art in general is a solid investment. “As an economist, that bothers me,” Moses says. “Because I have no idea what the non-auction market is doing, since there’s no transparency of prices.”

Worse, to the extent that the Mei-Moses data tell us much about contemporary art, it’s hardly encouraging news for investors. Once the professors realized how focused the buying public is on contemporary art, they folded in London auction records and had sufficient data to analyze the postwar and contemporary categories. “That market is less like the S&P 500 than like biotech start-ups,” says Moses. “The return can be very high, but so is the volatility.” In other words, caveat emptor.

Crash-Proof-Market Theory No. 4

Diversification As a Safety Valve

A more plausible theory—because it does not postulate an endless boom—points to the more diversified market created by a growing number of galleries and collectors and the viability of previously market-marginal art forms such as video and photography. According to this logic, the new art market no longer resembles a monolithic market sector (like, say, oil) but rather a more diversified category (i.e., energy in general, including everything from oil and coal to solar-power start-ups).

In this paradigm, there’s a constant process of mini-corrections, as some genres rise while others fall. A current example: Leipzig School painters stealing the spotlight from the many Düsseldorf Akademie photographers, such as Andreas Gursky and Elger Esser, whose photos seemed to have been carpet-bombed onto art-fair floors in the late nineties. Now? Not so much. Likewise, the boom in Japanese artists has flagged. “For a while, there were twenty [Takashi] Murakamis and [Yoshitomo] Naras going around each auction season,” recalls Lutz. “Now, suddenly, we’re not seeing as many.”

But can the cooling of certain sectors function as a safety valve, intermittently letting off enough steam to prevent the bubble’s exploding? No chance, says Moses. “A rising tide raises all ships, but a tsunami sinks them all,” he explains. “Look at stocks and bonds, which have enormous diversification. When NASDAQ went down, there were one or two winners, but there were a lot of sick puppies. Is the art market a little more robust because it’s more diverse? Sure. But it’s not possible that there wouldn’t be an overall drop because of that.”

Crash-Proof-Market Theory No. 5

The Japanese

Last (and certainly least logical), there’s the yellow-fever theory, which cites the irrational buying patterns of Japanese investors as the driving force of the last boom and subsequent bust, after their sudden disappearance owing to Japan’s violent real-estate crash. So now that they’re not behaving like that anymore, the logic goes, the market is safe. This overlooks the fact that Japanese buying in the eighties was strongly focused on Impressionism, not the stars of Soho. And in any case, there’s plenty of other clueless money in the market. Within the space of three days, two major art consultants declared to me, totally unprompted, “The hedge-fund guys are the new Japanese.”

“Right now, you hear people carefully parsing all the reasons why this situation is not the same as the last boom,” Glimcher observes. “But the basic currency of the art market is the same: The artists makes art, we stick it in a room, people buy it.”

Predicting when a slowdown will come is well-nigh impossible, but this much is safe to say: Bad things will happen at the moment when the upward push of aggressive pricing intersects with a flagging supply of neophyte buyers. And the brutality of that intersection will affect where along the correction-contraction-crash continuum the market lands.

Whenever insiders discuss nightmare market scenarios, they tend to start with the hypothesis of bad sales back-to-back at Christie’s and Sotheby’s. Once limited to work at least a decade old, auctions commonly now feature works only three or four years out of the studio. That makes them a market fulcrum. “Perception triumphs over reality,” says Westreich, noting that the auctions still represent only a small fraction of total contemporary-market activity. “If things sell for less than expected, we get nervous. People start saying, ‘Holy mackerel! It’s all coming apart.’ ”

In part, that’s because an artist’s failure at auction is totally transparent, whereas weak fair or gallery sales can be easily concealed. “I’m worried about the herd mentality among collectors,” confides international-capital-markets expert Amir Shariat, one of London’s more active young collectors. “I wonder, if something goes wrong with a few big-name artists at auction, could that trigger a crash?”

“As an asset market, art remains extremely illiquid. People forget that illiquid doesn’t mean ‘low price.’ It means ‘no price.’ ’’

If the market does go south, it’s likely to go fast, because the defining characteristic of the current art world is speed. “I only know three or four collectors today who won’t buy a work they’ve only seen as a J-PEG,” says Los Angeles and Berlin gallerist Javier Peres. “Whereas my grandparents would reserve a Picasso and not decide whether to buy until six months later, when they made it to Geneva to see it. But the flip side is that when things start tumbling, they could tumble really fast.”

At the first sign of a serious downturn, pure speculators would disappear almost immediately, alongside the legions of private dealers and art consultants currently skimming consignments and commissions off the top of the frothing market. “In the late eighties, we had private dealers up the wazoo, and then suddenly that whole layer evaporated,” recalls trader turned art dealer Kenny Schachter of London. “Some that I knew became gemologists, others went into real estate. The big question with a crash is, ‘How fast will the speculators bail?’ Because the trading mentality says, ‘Cut your losses.’ ” Yet most speculators will find they can’t sell their work. Not to the galleries facing cash-flow woes, and not through auction houses wary of unsellable consignments. “As an asset market, art remains non-transparent, overly prone to taste and fashions, and extremely illiquid,” notes Shariat. “People forget that illiquid doesn’t mean ‘low price.’ It means ‘no price.’ ”

Beyond the rapid exit of the froth-skimmers, the impact on other players is less clear. “It will be the same as in the early nineties but much more wholesale, because the art world is larger,” Westreich predicts. Glimcher is likewise unflinching: “Good artists and good galleries will go by the wayside. The unfit get weeded out—but so do some of the fit, unfortunately.”

Those expensive new Chelsea leases and mortgages could quickly become millstones; in the early nineties, many among the first wave of closures were dealers who had recently expanded into larger spaces. Much will depend on the gallery’s coterie of hard-core collectors. “When a trend is over, the first people to put things into storage are museum curators,” explains Berlin dealer Matthias Arndt. “But collectors will continue to buy and show an artist they find personally interesting. So the young galleries who make things so difficult for collectors now may suffer the most later.”

Among the galleries that survive, a slowed market will unleash a time of abrupt change, owing to the art-market taboo against lowering an artist’s prices, because such adjustments make past prices—supposedly based on art-historical standing, not market trends—seem indefensible. The art market has a mechanism for handling such dilemmas: a de facto free-agency period, during which artists can shift galleries with minimal rancor, allowing prices to be adjusted to new market realities.

So in the event of a correction, contraction, or crash, which particular artists will best maintain their value? The answers can only be guessed (and none given here should be considered investment advice). But some educated speculation is possible (and irresistible). “Personally, I’ve made a list of twenty artists whose market I think would survive a crash,” says London private dealer Nicolai Frahm, 31, a frequent bidder on work at high-end contemporary auctions. “I’d say only five to eight of those are a sure thing.” Though Frahm’s not about to make his list public, his logic in making it follows the conventional wisdom: Only artists whose work looks good and also has art-historical significance—for its technical or conceptual innovation—survives a crash. “These hedge-fund guys are not so sophisticated, so of course they’re buying lots of pretty pictures,” points out Valentine. “But look at the eighties stars. Who do we think is important now? Gober. Koons. Maybe Cindy Sherman. Maybe Richard Prince.”

All four are artists Westreich was buying early on. “The bigger the idea, the longer the career, because that’s what makes an artist’s work relevant, rich, and rewarding,” she says. “I never trust the multitudes, because the most radical ideas take the longest for the market to absorb.” Among today’s crop, her bets are on brainiac artists such as Simon Starling, Keith Tyson, and Jan de Cock, who constantly play with the border between art and other fields, such as science and architecture.

That same logic bodes well for the late German painter Martin Kippenberger—not an easy artist and one whose market lay pretty fallow until recently—but unquestionably a seminal figure for European artists, much like Joseph Beuys a generation earlier. Likewise, Thomas Ruff seems a surer bet among photographers than Andreas Gursky, because Ruff has relentlessly pushed at the boundaries of the medium (and because Gursky’s name is so linked to the late-nineties photo hype).

Damien Hirst is a tricky call. On the one hand, he’s flooded the market with work, most of it churned out by his assistants, and the prices are astronomical. Also, you’d be hard-pressed to find a critic willing to publicly praise his recent work. On the other hand, as the spearhead of the Young British Artists and clear successor to Warhol as an art-world icon, he’s impossible to discount. Likewise, Murakami seems solid, if less for the art itself than for his role in pulling Japan into the contemporary-art world and for his global approach to production. “To me Murakami’s more significant than Hirst,” Valentine says. “Because just as Koons took Warhol’s ideas and changed how we look at art, Murakami took Koons’s ideas and pushed them further. And the objects themselves are compelling.”

Schachter, who charts certain artists’ careers obsessively, leans toward Richard Artschwager and John Baldessari. “You can still get a major piece for $100,000 to $200,000,” he says. “Which by comparison makes them underpriced.”

By contrast, he’s wary of artists whose markets have risen very quickly at auction, such as John Currin and Elizabeth Peyton. “I wonder if those prices would hold up even now,” he says. “Or look at Cecily Brown, who is talented and a nice person, but to me her work looks like derivative de Kooning.” Granted, Schachter’s known as an art-world provocateur, both loved and loathed for making such pronouncements. But after requesting anonymity, one high-end dealer walks me through the market favorites, downgrading many of the same artists: “Marlene Dumas? No. Currin? No. Chris Ofili? No. Elizabeth Peyton? She’s interesting, but not at those prices. Peter Doig? No. Gursky? Never.”

Of course, opinions vary. “You can make a compelling case for Currin’s position among American painters,” counters Valentine. “To me, he’s at least as profound as some of today’s Conceptual artists. But I’m profoundly skeptical of the Leipzig School. Most museum curators aren’t taking them that seriously.” Count Schachter among the Leipzig-skeptical, too: “I just don’t see how those painters can meet the expectations created by those astronomical prices.”

“I’m sitting on a stack of great work, and I have plenty of cash. I can’t wait for these idiots to get out of this market.”

Even the Leipzig School’s main dealer, Gerd Harry Lybke, acknowledges the issue. “We saw what happened before with people like Schnabel, so we’re not raising prices at the gallery too much,” he explains. But the resale market’s another matter; once demand gets too high, even a dealer as cunning as Lybke has a hard time keeping some of his collectors in line.

For all the suffering a slowdown will unleash, only a real-world apocalypse would stop sales altogether. During the early nineties, some artists continued to set auction records. Music mogul David Geffen built much of his collection—considered among the best for American art—during that period. “I’m sitting on a stack of great work, and I have plenty of cash,” says another world-class collector. “I can’t wait for these idiots to get out of this market.” Many art-world veterans say they’ve had enough of the seller’s market. “It’s become extraordinarily unpleasant to compete for work in this market with people buying for social-status reasons or financial speculation,” Valentine explains. “It would be better for things to come into alignment. Why should a Matthias Weischer sell for the same price as Richter?”

Even Glimcher, a seller in this seller’s market, is a little tired of it. “In the VIP room at Art Basel last summer, I overheard these young dealers, people who had booths in the fair, talking about what they’d do when the market crashed—Hollywood producer, agent, etc.,” Glimcher recalls, his voice a mix of outrage and amusement. “I turned around and said, ‘Good riddance. Get out now!’ ”

Yes, the art world will shrink, but never to its early-nineties size or even its late-eighties boom size. Because if the art market is an expanding bubble, inside it there’s a harder-density core, also expanding, composed of lifetime collectors and institutions with impregnable funding. Until the bubble bursts, however, it’s hard to judge the core’s size.

But at a moment when beating up on the Whitney Biennial’s and the Armory Show’s same-samey-ness has become an art-world parlor sport in New York, here’s a cheering thought: Historically, bad markets tend to produce better art—there’s less pressure on artists to produce and fewer temptations to sell out, and they’re dealing only with collectors and galleries willing to ride out the hard times. “I learned to do a gallery on no money when I started in 1999,” Feuer points out. “It totally sucks, but it’s doable. At the worst, I could sell art out of a studio apartment.”

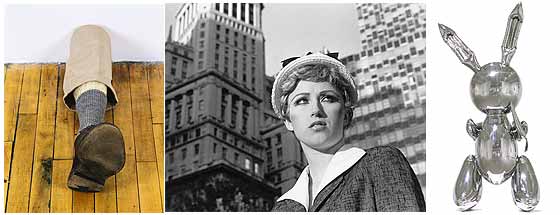

Three Artists Who Survived the Last Bust

Robert Gober

A true art-world intellectual, Gober makes quietly ambitious work that is hardly a quick read, but those who make the effort tend to be convinced.

Cindy Sherman

Her constant playing with identity and popular culture have made her a curatorial and collector favorite.

Jeff Koons

Master of the media game, he’s prized by fans for redefining artistic practice. Plus it’s hard to resist someone so shamelessly over-the-top.

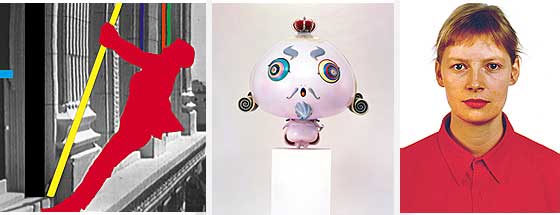

Three Artists Who Will Survive the Next Bust

John Baldessari

Though the market for him took time to develop, Baldessari’s influence on future artists has steadily swelled to living-god status, cementing his spot in art history.

Takashi Murakami

Beyond perfecting the artist-as-entrepreneur role, Murakami has also served as a one-man bridge between Japanese pop culture and Western contemporary art.

Thomas Ruff

Though his images are often less quickly appreciated than those of his Düsseldorf Akademie rival Andreas Gursky, Ruff has relentlessly pushed the boundaries of photography.

Plus:

• Three Artists Who Survived the Last Bust

• And Three Artists Who Will Survive the Next Bust