This is a great puzzle,” says Will Shortz.

The crossword editor for the New York Times is giving me an advance peek at the Sunday puzzle he will publish a week later. “See, now this grid is jam-packed with fresh uses of language,” Shortz says, sitting in his home office amid stacks of reference books like Brands and Companies 1995 and The Encyclopedia of American Cars. “MRPEANUT, great answer. GIJOE, great! Only five letters, yet it has a J in the middle—very pretty.” Shortz has only one complaint about the puzzle: It uses the abbreviation nle for “NL East,” which he thinks is too obscure. It only took him a few minutes to deftly scribble in a new tangle of words. AAMES, of “Willie Aames,” turns into AIMAT; AMMO becomes OLIO; and NLE becomes ULA—a “diminutive suffix,” such as at the end of “spatula.”

Me, I didn’t know ula was a word. But Shortz’s fan base generally does—the millions of word freaks who revere him as the nation’s master of linguistic play. In his thirteen years at the Times, Shortz has revolutionized the paper’s immensely popular crossword. Twenty-five percent of the people who pick up The New York Times Magazine on Sundays flip to Shortz’s puzzle first. This week, his reputation as a word-nerd hero will be cemented with the premiere of Wordplay (see David Edelstein’s review), a documentary that profiles Shortz fans as diverse as Bill Clinton, Jon Stewart, and Yankees pitcher Mike Mussina. They regard his puzzle as the last true showcase for elegant language, sparkling wit, and groan-inducing puns.

Yet here’s the weird thing: If you pump Shortz’s name into Amazon these days, you won’t find his many crossword books at the top of the list. You’ll find something else—his books of Sudoku, the arriviste number puzzle that became a smash hit last year. Sudoku is the complete antithesis of the crossword: You fill in a nine-by-nine grid with the numbers one through nine so that no digit repeats in any column or row—nor can there be any repeats in any of the nine three-by-three boxes that make up the whole grid. It may sound complicated, but you can play it even if you’re completely illiterate—hell, even if you’re innumerate, since Sudoku doesn’t even require math. It is the ultimate puzzle for a postliterate world.

And it is making Will Shortz a mountain of cash. St. Martin’s, his longtime crossword publisher, began issuing his Sudoku books last year; it is now a 50-book series that has sold a mind-bending 5 million copies. Across the board, Sudoku has sold so prodigiously that it has pushed nearly every crossword book off the best-seller charts of Nielsen’s BookScan. At the end of May 2005, before the Sudoku storm arrived, a crossword volume was No. 1 on the charts for adult “games” books, and six of the other 49 titles were crosswords. One year later, Sudoku had wiped the slate clean: Forty of the top 50—including the top spot—were Sudoku books, and more than a third of those were Shortz’s.

All of which raises an interesting question: Has Will Shortz’s moment in the sun arrived—just as the crossword is being eclipsed?

Shortz is a slender, mustachioed man with a perennially impish grin—almost precisely what you’d expect a philosopher of puzzles to look like. “Puzzle people like to put things in order and to complete things,” he tells me. “Of the natural problems we face every day, very few have concrete solutions. We just jump in the middle and muddle through. But with a puzzle, you have that feeling of completion, which is very satisfying. You have not a solution but the perfect solution.”

Shortz loves things that work cleverly. He has decorated his Jazz Age mansion in Pleasantville, New York—headquarters for his puzzle empire—with antique furniture that was designed in reaction to the industrial age. “It’s all handmade, without using any nails,” he points out as he takes me on a tour.

Crosswords hold much the same appeal for him. They too are handmade: “Constructors,” word aficionados from all walks of life, craft the puzzles in their spare time and mail them to Shortz, praying he’ll publish them. He receives about 75 submissions a week but has exacting standards: A puzzle must be “jam-packed”— his favorite phrase—with unusual, new, or unexpected words. Though everyone assumes the killer Saturday and extra-large Sunday puzzles are the hardest to make (since the Times puzzles escalate in difficulty during the week), Shortz argues that Monday is difficult, too, because finding a fresh combination of well-known words is fiendishly hard as well.

Sitting at his computer, Shortz pulls up one of his favorite puzzles, by Brendan Quigley, a 32-year-old rock musician in Boston whose work Shortz frequently publishes. Quigley is famous for being the first constructor in the nation to use a new piece of slang or a brand name. This puzzle uses QUIZNOS—the submarine-sandwich chain—in the most challenging position possible, the bottom right-hand corner. NASDAQ and PEZ connect with the tricky final Q and Z. “Brendan’s grids are just packed with fresh uses,” Shortz says.

Shortz was a veteran of the puckish Games magazine, and when he moved to the Times in 1993, he decided the crossword had become “stodgy, old-fashioned, humorless, not particularly interesting.” He cut down on the use of antique words and began instituting deceptive, allusive clues. (His all-time favorite clue: For SPIRAL STAIRCASE, the phrase “It might turn into a different story.”) He also pioneered the use of “product” words like MEMOREX or XEROX. A flood of letters ensued, many praising him, some furious. One letter he reads aloud during the documentary actually calls for his execution.

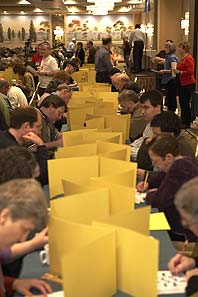

Such are the tribal passions of crosswords. It is a culture at once geeky and avowedly elitist, “a slice of the intelligentsia,” as Jack Rosenthal, who hired Shortz at the Times, puts it. Puzzlers sneer at lesser crosswords, rank newspapers by their puzzle quality, and outright despise the trend toward computer-generated grids, which inherently have less-clever combinations of phrases. (As Jon Stewart jokes, “I’ll solve, in a hotel, a USA Today [puzzle], but won’t feel good about myself.”) Bill Clinton—famous for completing the Times crossword in a few minutes, flawlessly and in ink while simultaneously arguing with political leaders on the phone—views the crossword as nothing less than an analogue for life. He tackles political dilemmas the same way he tackles a puzzle: “You start with what you know, and you just build on it.” This is the documentary’s precise conceit—that through the crossword we can see the spirit of an entire class of people, the nation’s highbrows, the wonks who cherish vocabulary and wit, prize precision and accuracy, and who believe it is a moral good to read widely in the culture.

If one can see a national spirit in the puzzles we play, it’s impossible to ignore the blitzkrieg rise of Sudoku. The numbers game has been around since 1979, when it was first published by Dell, the puzzle-magazine company. But it broke only just over two years ago, when Wayne Gould, a retired judge and lawyer, persuaded the Times of London to start running them. They got an immediate uptick in sales. Within months, every paper in Britain had piled on the bandwagon. (At one point, the Guardian ran a Sudoku on every single page of an issue.) The puzzle spread to New York in April of last year when the Post started running it. Today, virtually every major daily in the country—with the notable exception of the New York Times itself—has a Sudoku.

Has Will Shortz’s moment in the sun arrived—just as the crossword is being eclipsed?

Shortz was drawn into the craze when St. Martin’s called him in a panic last June. It demanded he produce three books of 100 Sudoku puzzles each in ten days, which he did with the help of a computer programmer in the Netherlands. The first book sold out 25,000 copies instantly; reprint upon reprint followed. This summer, St. Martin’s had a Sudoku series by Shortz, with a million books rolling off the presses every month. The puzzle world has never seen sales like this before. Shortz’s crossword titles were deemed rocketing success stories if they sold 150,000 copies in four years.

“This is turning our company upside down. This is the biggest thing we’ve ever had,” says a harried Lisa Senz, vice-president and associate publisher of St. Martin’s. “And it’s not slowing down. If anything, it’s accelerating.”

What precisely is the allure? Shortz argues that Sudoku has a secret psychological hook. While solving them, you tend to get bogged down midway—then suddenly break through, fill in the last bunch of empty boxes in a row, bang bang bang. “It gives you a satisfying feeling to be rushing at those squares,” Shortz says. “And immediately you want to do another one. That’s the key to why they are so addictive.”

Yet it is also, in a way, a total negation of crossword culture. Sudoku requires no knowledge of trivia or history, no literary bent. Sudoku doesn’t care what you know, smarty-pants; it just wants you to act like a logic cruncher, a Pentium chip. “It’s not what you know—it’s how you think. That’s what Sudoku tests,” says Gould. Its nonlinguistic nature is precisely why it has spanned the globe so quickly: A puzzle created in the U.S. can be sold to China or Germany with no translation necessary, and American immigrants who don’t speak good English can happily solve Sudokus.

Less charitably, one could regard Sudoku as the lowest common denominator—a puzzle for a nation whose citizens no longer presume to have any culture in common. “I don’t want to call it a dumbing down of society,” Abby Taylor, Dell’s editor-in-chief, says delicately, but she has noticed that nonlanguage puzzles like Sudoku—or nondemanding ones like word searches—have been steadily increasing in sales, while sales of difficult crosswords remain flat.

So as you’d imagine, many crossword fanatics regard Sudoku with the disdain a jazz purist might have for American Idol. “It interests me about one-tenth as much as the crossword,” Rosenthal says with a shrug. For crossword constructors, Sudoku represents a robotic outsourcing of the puzzle trade. Sudoku requires no individual artistry, no exquisite handcrafting; the puzzles are simply cranked out by computers, the Coca-Cola of conundrums. Brendan Quigley says that while he enjoys Sudoku himself—he plays three or four daily—he suspects the upstart competition has piqued many other crossword constructors. “People are only going to spend so much time a day on a puzzle, and it’s either going to be a logic puzzle or a crossword, right?” he says. “A lot of the Old Guard don’t want to hear that, but it’s the truth.”

Shortz remains diplomatic about the Sudoku Godzilla: “We’re living in a golden age of puzzles,” he declares, proclaiming himself an equal-opportunity puzzle fancier. Mind you, I’m never exactly sure how Shortz really feels, because when the conversation turns to Sudoku, he never quite lights up the way he does when we discuss a nicely jam-packed grid, crackling with wit and wordsmithery. Wisely, he’s not criticizing a game that is making him rich.

Shortz himself is diplomatic about the Sudoku Godzilla. “We’re livingin a golden age of puzzles,” he declares.

Perhaps the biggest puzzle of all is why the Times itself—which, let it be noted, employs me as a contributing writer for the Times Magazine—hasn’t started publishing Sudoku in its pages, despite the fact that Sudoku is a proven circulation booster. There are three daily Sudokus on the Website, but the puzzle has yet to make an appearance in print. For his part, Shortz says he’d be happy to put Sudoku in the Times, except that the management hasn’t asked him to. The reason, he figures, is that there’s no way to do Sudoku in a sufficiently Timesian fashion.

“Anything the Times does has to be more cultural and intellectual than anybody else’s version of it. If they’re going to do a gossip column, it’s going to be more highfalutin than anyone else’s gossip column,” he says. “But how do you improve Sudoku? I don’t think you could do that. The puzzle is what it is.”

It is what it is. A nice epigraph. Or perhaps a clue.