The Nightsong of Wolfman Jack

“…Now that radio’s hit the big time again, Wolfman Jack is out for all he can get. ‘I’m what they call big business,’ he explains…”

By Ellen Stock

“…Now that radio’s hit the big time again, Wolfman Jack is out for all he can get. ‘I’m what they call big business,’ he explains…”

The news is over. It’s 7:08 p.m. in Studio 2B, and the engineer calls, “Show time!” The lead-in begins: “Hearin’ good music on the radio. Wolfman Jack’s playin’ rock ‘n’ roll. You can lose your san-i-ty. Wolfman Jack’s on NBC! Here come da Wolfman, y’understand?”

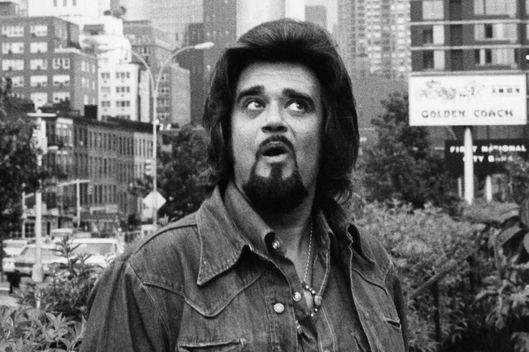

The red bulb lights up, and bursting into everything comes: “Hi, everybody! Hi, hi, hi! Hi, everybody! Yes, yes, yes!” The Wolfman is on the air—his eyes wild, his nose scrunched up, his voice an explosion of static and growl, a hatchery of black-accented patter and insinuation.

“Good evening to you once again,” he scratches. “The Wolfman Jack Show is going to carry you on a carefree, airy journey up here where the air is raaare!” His eyes close ecstatically.

The light goes off, the engineer spins “Gypsy Man,” and Wolfman Jack picks up the phone.

“Are ya naked, baby?” he purrs into it. “Get naked, baby!” His mouth curls around the mike.

Until American Graffiti opened last month—the movie in which Wolfman Jack plays himself, the West Coast disk jockey/ guru—he was pretty much a mystery to New Yorkers. Now that radio’s hit the big time again, he’s out for all he can get. “I’m what they call big business,” he says.

Indeed. This broadcasting phenomenon is syndicated on 1,453 radio stations in the United States, and on 420 stations in 42 foreign countries. He’s host of The Midnight Special every Friday on the NBC television network, and now he’s at WNBC radio, live, reaching 37 states a night, six nights a week from seven to midnight.

“I’m here because it’s my hometown,” the Wolfman explains. “New York is turning into chaos. It’s disgusting, what’s happening. I want them to put down the knives and the bats, stop the killing. I want to bring love and happiness. I’m not in it for the money.”

Sitting in the studio now, wearing tight black appliquéd jeans, black cowboy boots, a black-and-red nylon shirt, and two turquoise rings, he’s having a very good time.

Across from him is his engineer. Surrounding him, pampering him, are three hairy go-fers. They’re the ones who pull his records from the cassette racks, the ones who feed him his Lucky Strikes, his water in tiny paper cups and his ad libs from little piles of index cards entitled “Love, Life & Wisdoms” and “Oldies Rap” and “Phone Rap” and “Surrounding Cities and States” and “General Momentum.”

“This is WNBC, radio 66, New York City,” the Wolfman growls, “and it’s waaarrm outside. It’s 400 degrees in Brooklyn, 600 in Queens. Everybody’s sweatin’ and gigglin’ and dancin’ and lovin’.”

NBC used its power and delayed the New York premiere of American Graffiti to coincide with the New York premiere of Wolfman Jack. The show started on August 6. A week before that, the newspaper ads started running (“Cousin Brucie’s days are numbered! Wolfman Jack is on the prowl”), and three days before that, the station started playing promotional welcomes taped, for free, by the Wolfman’s friends: John and Yoko, Mac Davis, Neil Diamond, Helen Reddy, David Gates, Smokey Robinson, Tommy Hart.

His name is Robert W. Smith. The W, he says, stands for Wolfman. He was born 35 yeas ago in Brooklyn, and went to high school for one year, during which he was a member of the Taggers gang. “I was a great shot with a zip gun,” he says. “I was a baaaad ass. But I never got a record because I was too smart.”

His one non-gang activity was helping out at a radio station in Newark. “I had a fascination for radio. I hung around WNJR and learned a lot.”

When he was fifteen, Robert W. Smith moved to Levittown, where he worked in a carwash and went steady with somebody named Virginia. At sixteen, he decided to go to Hollywood and become a star. He got waylaid when his 1947 Buick died in Washington, so he took a job as a Fuller Brush man and taught control-board technique at a broadcasting school.

Fame came to Robert W. Smith in Newport News, Virginia, where he became “Big Smith With the Records” and went on the air every morning at six ringing a cowbell. When the station changed its sound from rock ‘n’ roll to Sinatra, Big Smith changed his name to Roger Gordon.

Next he went to Shreveport, Louisiana, where he ran the station. “But I’d always been laboring with the Wolfman thing,” he says. “I had this big fascination with XERF, a big Mexican station that covered the whole North American continent—250,000 watts, clear channel.

“They were doing mail-order programs. They’d sell songbooks, record packages. I went to the station—it was in Villa Acuña, in the state of Coahuila. I was on from midnight to 4 a.m. I got no salary, but I made a commission on every mail-order product.”

Soon thereafter, there were union problems and a gun battle he refuses to discuss. So he went to XERF in Tijuana, then to KDAY in Santa Monica. When he got to NBC last month, he had close to 100 million listeners.

Who are they? “Mostly, they’re women,” Wolfman says. “I get a lot of women because I’m honest. I don’t try to really appeal to men. A lot of young girls respect me. They call me to talk about their problems. I don’t take advantage. I try to help.”

The Wolfman has seen American Graffiti twice. “It’s a piece of history, a piece of Americana,” he says. As the record-spinning hero of director George Lucas’s youth, the Wolfman was written into the movie and is proud of his role. So proud, in fact, that he did it for a flat fee and spent $10,000 to promote it. “We wanted this movie to take off,” he says. “It kind of enshrines the Wolfman picture. It’s what I’m all about. Nonsensical, but loving. The rebel with a cause: love and happiness.

“I’m honest, real, up front. I party. I get high. I’m a street person. You understand what I mean? I preach love. When you do right, you come out right. When you love, you live."

*A version of this article appeared in the September 17, 1973 issue of New York Magazine.