Anatomy of a Drug War

“…The mob’s decision to re-enter the narcotics business after a ten-year ban is expected to escalate further what is already open warfare among New York City’s independent junk dealers…”

By Nicholas Pileggi

“…The mob’s decision to re-enter the narcotics business after a ten-year ban is expected to escalate further what is already open warfare among New York City’s independent junk dealers…”

After a series of secret meetings in August, the city’s Mafia leaders decided to end their ten-year self-imposed prohibition and re-enter the narcotics business. It was a decision based on the fact that the profits in drugs today are greater and the risks more remote than ever. Long before the public was aware that the police department property clerk’s office served as a major drug supply center, Mafiosi knew that law enforcement in the area had broken down. It was the Mafiosi, after all, who were buying back much of the same heroin and cocaine that was being seized from them by narcotics agents.

The decision, aside from its probable social consequences, is expected to escalate further what is already open warfare among the independent junk dealers who now control the importation and distribution of drugs in the city. In the last two years, for instance, there have been more than 250 murders of middle-level non-addict pushers. There has been, in fact, even without the Mafia’s heavy hand, an exotic orgy of violence among the city’s free-wheeling dealers, wholesalers, smugglers, importers, corrupt cops, double agents, and street-corner pushers. There are parts of Bedford-Stuyvesant in which black heroin dealers control so many killers that even state legislators and local political leaders admit privately that they are terrified to speak out against specific individuals.

There are streets in Harlem, the South Bronx, and around the Sunset Park area of predominately white working-class South Brooklyn where pushers openly argue over choice sidewalk locations, like chestnut vendors outside Radio City. In upper Manhattan’s Washington Heights area where Cuban dealers have established themselves in some of the bars along Broadway, from 138thStreet north, daily shootouts have paralyzed police action with sheer volume. In the Bronx, wholesale junk markets on Walton Avenue off the Grand Concourse continue to proliferate even though police records show repeated arrests and harassment.

The drug world seems to gain strength from adversity. It is an environment of thoughtless, mechanical, clockwork violence. Since many of the deaths occur in black, Puerto Rican and Cuban neighborhoods, however, the media and the public have missed most of the fireworks. Occasionally, a murder involving middle-class whites, an undercover cop or a Mafia soldier makes the papers, and the Six-O’Clock News. On November 1, 1972, for instance, there was a front-page story in The New York Times about an N.Y.U senior and his roommate, a suspected drug dealer, being murdered in their apartment across the street from the school’s uptown campus. On the same day, a typical day, the following drug-related homicides and assaults also took place in the city, but without any mention in the press (the list does not include addict street crimes such as muggings and holdups):

John Spann, 35, shot and killed at 111thStreet and Fifth Avenue by an unknown man hiding in a doorway; Ronald Lucas, 24, stabbed to death in front of 590 East 21stStreet, Brooklyn; Luis Rivas, 28, shot and killed while standing in front of 54 Jesup Place, the Bronx; Bartolo Courasco, shot and critically wounded by two men from a passing car while standing on Columbus Avenue, near West 82ndStreet; Clark Jackson, shot and seriously injured at Eighth Avenue and 114thStreet; Robert Smith, shot and seriously injured while standing in front of 19 West 126thStreet; Hector Santiago and Guillermo Rodriques, shot and critically injured by two men in a passing car at the corner of Graham and Seigel Streets, Brooklyn; Israel Ortiz and James Delgado, shot and critically injured while standing in front of 1228 Morris Avenue, the Bronx; Eliot Roman, shot while standing on the corner of Vyse Avenue and East 179thStreet, the Bronx.

--

The real danger for the city’s drug dealers, quite obviously, does not come from the law. As the center of the nation’s drug traffickers, New York has become Junk City, a predatory scene of unrivaled violence, official corruption and Byzantine plots. No army of anthropologists could ever have constructed a laboratory habitat better suited to the enrichment of the Mafia’s style. The very chaos of the city’s drug business has made it a temptation to the mob.

When the Mafia abandoned the narcotics business in the early 1960s it was because too may bosses suddenly found themselves going to jail for drug conspiracies hatched by their underlings. Carmine Galente, John Ormento, and Vito Genovese were all top men who were jailed during that period. A few Mafiosi had continued dealing in narcotics, even during the boss-imposed ban, and today increasing numbers of the mob’s aggressive and avaricious young Turks refuse to accept the timidity of rich godfathers as enough reason to stay out of narcotics. The profits are simply too great. Dealers in the United States who paid $18,000 for a kilo (2.2 pounds) of 80 to 90 per cent Turkish heroin in 1971 are now offering $40,000 for a kilo of Asian heroin that is only 25 per cent pure. An investment of $500,000 in Corsica, São Paulo or Saigon can return $10 million on the city’s streets.

Compared with other illicit Mafia businesses, importing and distributing drugs is administratively painless. Junk deals are consummated once or twice a year, and exposure to the public, corrupt cops and underworld employees is minimal compared with such vulnerable day-to-day operations as bookmaking, policy, and loansharking.

“…In the last two years, there have been more than 250 murders of middle-level, non-addict heroin and cocaine pushers…”

Someone has to take those bets, count the money, deal with the telephone installers, to say nothing of paying off the winners, cops, landlords, bail bondsmen and disgruntled Mafia employees. In the drug business, there is very little exposure and thus a minimum of vulnerability. In addition, there are now very few hoods around who do not know how easy it can be to smuggle contraband into the United States. Along the 1,200-mile Canadian border between Erie, Pennsylvania, and the Maine coast, for instance, there are two Great Lakes (Erie and Ontario), Niagara Falls, Lake Champlain, the St. Lawrence Seaway, scores of small waterways, 100 unguarded border roads and 1,000 rural airstrips upon which a small plane can land undetected. This entire stretch is patrolled by 100 border guards, with never more than twenty of them on duty at one time.

Just as the Mafiosi had replaced Jewish racketeers who controlled the narcotics business before the end of World War II (“smack” as slang for heroin is derived from the Yiddish schmeck, or smell), a loose amalgam of multi-racial and multi-ethnic entrepreneurs took the Italians’ place in the early sixties. Blacks, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Argentinians, Brazilians, and, lately, Chinese distributors moved in on the wholesale and importation level. Independent black junk dealers like Julian St. Harrison, Gerald Hartley, Leroy Barnes, and Robert Stepney have developed their own Latin-American connections. Harrison, at 53, is known to police as a ten-kilo man who specializes in supplying out-of-towners from his East 215th Street headquarters in the Bronx. Hartley and Barnes are both considered major traffickers, Barnes having been a front for the East Harlem Mafiosi before they got out. Stepney, who police say commutes from Teaneck, New Jersey, to Bedford Stuyvesant every day, is another of the city’s top dealers.

The money being made by black racketeers in narcotics, of course, is finding its way into other illegitimate enterprises. Blacks are not only running their own policy and loanshark operations in areas that were once Mafia controlled, but they have begun moving into legitimate businesses as well. Bar-and-grills, drycleaning shops, liquor stores, even ghetto tenements are being swallowed up by black racketeers in payment for gambling and loanshark debts, a pattern of upward criminal mobility ominously familiar to the Mafiosi themselves.

--

One of the biggest Cuban operators in the city today is Rene Texeira, who lives in the Bronx but controls, along with Regilio Fernandez, another Cuban, most of the trafficking in northern Manhattan and New Jersey. The Mafia’s greatest problem in retaking their netherworld interests will undoubtedly come from the Cuban racketeers. In West New York, Union City and Hoboken, New Jersey, as well as Washington Heights and much of upper Manhattan, junk has been controlled by Cuban gangs since the Mafia families of Simone Rizzo (Sam the Plumber) DeCavalcante and Joseph (Bayonne Joe) Zicarelli were decimated by continuous Federal harassment and jail. The Cubans, meanwhile—some with a paramilitary training left over from their Batista, anti-guerilla days—have become a powerful criminal group as well organized, some say, as the Mafia itself. The Cubans’ greatest enemies at present, however, are the city’s Puerto Rican racketeers, who are in direct competition for the Latin junk market and for gambling and loan-shark operations.

On Manhattan’s Upper West Side, with his base of operation around Broadway and 110thStreet, Anthony Angelet, a 54-year-old Puerto Rican racket boss, is holding the fort for Raymond (Spanish Raymond) Marquez, who is in jail. Lionel Gonzalez, another of the city’s powerful Puerto Rican dealers, concentrates his activities in the South Bronx, more specifically from his headquarters along Southern Boulevard between 149thand 150thStreets. In Brooklyn, the top Puerto Rican dealer has been identified as Jose Rosa, whose connections along Fourth Avenue in South Brooklyn are as good as his connections on the island of Puerto Rico. He is, in fact, the island’s key supplier. These top dealers are so carefully insulated from their day-to-day operations that it is extremely difficult, despite almost daily harassment and questioning by the police, to land any of these men in court.

Further complicating the Mafia’s takeover plans are the Chinese. Ten years ago, when the Italian-American Mafiosi left Junk City, the main suppliers were Sicilian, French and Corsican. By controlling these suppliers, the Mafiosi controlled the mount of drugs that entered the United States. During the middle sixties, however, increasing numbers of Chinese seamen began jumping ship in the United States with as much as ten kilos of heroin strapped to their backs. Suddenly, the poppy farms of Turkey, the smuggling routes through Sicily and Corsica, and the refineries in Marseilles were no longer the only sources. Today, it is estimated that more than half the heroin used in the United States comes from the Far East, much of it smuggled into the country by ship-jumping Chinese seamen. Customs and immigration officials say it is impossible to deal with the problem effectively. The relaxation of immigration rules has recently filled America’s Chinatowns with new inhabitants, and it is comparatively simple for a seaman with $50,000 worth of pure heroin to disappear in these communities. On April 11, seven Chinese were arrested in New York with eleven pounds of heroin, and six of the seven turned out to be ship-jumpers. The heroin was part of a 100-pound batch brought into the country by a European diplomat. On June 30, four Chinese were arrested in a Sunnyside, Queens, apartment trying to extricate eighteen pounds of heroin from behind a baseboard where two other Chinese had hidden it earlier in the year at the time of their arrest. And, on August 2, as the godfathers made up their minds to get back into the junk business, Federal agents arrested 60-year old Kan Kit Huie, the unofficial mayor of Chinatown, in a $200,000 deal involving twenty pounds of heroin, two Chinese businessmen, a Chinese ship-jumper, two Chinese-American undercover cops, 40 Federal agents using twelve unmarked cars and a seven-hour circuitous tour led by cautious Huie that took the entire entourage through the alleys, factory buildings and streets of the Lower East Side.

The Mafiosi explored a return to the drug trade about a year ago. Key men were given permission to make buys, and a few have been caught.

On January 18, Louis Cirillo, a Lucchese family associate, was indicted in Miami in a 1,500-pound multi-million-dollar heroin-smuggling conspiracy. On April 29, while searching through Cirillo’s Bronx home, Federal agents found nearly $1.1 million buried in the backyard and basement. On February 4, another Lucchese family associate, Vincent Papa, was arrested in the Bronx with $967,500 in a green suitcase destined for a 200-pound heroin buy. Papa had once served five years for selling narcotics and had a record of 26 arrests. On May 10, Joseph (JoJo) Manfredi, a Gambino family captain, was arrested along with two nephews and fourteen other men in a $25-million-a-year heroin operation that specialized in supplying several midwestern cities. On July 15, Michael Papa, Vincent Papa’s 24-year-old nephew, was arrested with another man for selling eleven pounds of cocaine to an undercover agent.

--

In addition to the unusual rash of Mafia-associated drug arrests, police began hearing rumors that a number of gangland killings were directly related to the mob’s re-entry into drugs. On August 10, for instance, the bodies of two of Joseph Manfredi’s nephews, one of whom had been arrested with him on May 10, were found in the deserted Clason’s Point section of the Bronx. The killing was apparently intended to insure silence in the drug case involving their uncle.

On July 16, when acting Genovese family boss Thomas (Tommy Ryan) Eboli was shot and killed on a Brooklyn street corner, it was at first suspected that his death had something to do with the Gallo-Colombo war. He had just walked out of his girl friend Elvira (Dolly) Lenzo’s Lefferts Avenue apartment, shortly after midnight, when two men stepped out of a yellow panel truck and opened fire, hitting Eboli five times in the head and neck. Since the killing, Federal agents suspect that Eboli was killed not because of a Mafia family feud, but because he was involved in a $4-million narcotics scheme in which he tried to withhold more than a million dollars. On April 29, when Federal agents dug up Louis Cirillo’s backyard in the Bronx and found $1,078,100, Eboli’s fate was sealed. It is now suspected that Eboli had withheld that sum from his peers, the very top-level Mafia financiers who had originally bankrolled Cirillo’s heroin-smuggling plan. As is customary in such cases, underlings like Cirillo are not held responsible for the greed of their bosses and are, therefore, spared. Eboli, however, knew better. “They had to blow him away,” an informer explained, “because he had held out on bosses. He had made fools of his own kind. The only thing that took them so long [Eboli was killed two months and seventeen days after the money was uncovered] was that they were probably trying to get him to replace the million so he could live.”

Other signs of the mob’s re-entry into junk were apparent when top Mafia bosses like Santo Trafficante of Tampa and Joseph Marcello of New Orleans suddenly took trips to the Far East. Federal narcotics agents, who have spotted both men in Saigon, Hong Kong, Singapore and Thailand, are almost certain that Asian connections were being established to supplement the mob’s traditional French and Corsican suppliers. Another indication was the appearance in New York late last year of Thomas Buscetta, a Sicilian-born man of many passports and the Mafia’s main South American connection. Buscetta was arrested in front of the United Nations as an illegal alien, but left the country after posting $40,000 bail. He was wanted at the time by Sicilian police for masterminding a 1963 massacre in which seven policemen and three civilians died. Today, Buscetta lives in São Paulo, Brazil, under the name Robert V. Cavalaro, and owns a fleet of 275 taxicabs and a string of luncheonettes. Slipping in and out of the United States almost at will, Buscetta was recently caught coming through the Canadian border at Champlain, New York, with an American, three Italian, and two Argentinian passports. While customs officials marveled at the fact that each of the passports bore a different name under his photograph, and as they searched his car, finding a Playboy Club credit slip, a booklet of lottery tickets and a reel of obscene film, Buscetta disappeared from the border patrol station.

Buscetta’s importance to the Mafiosi is twofold. He is not only their man in South America, but he also represents, at 44 years of age, just the kind of potential Mafia boss that old-world dons like Carlo Gambino would like to see take over the secret society. Gambino has been importing foreign-born Mafiosi like Buscetta for several years, and police intelligence officers suspect that much of the pressure being applied to organized crime leaders to return to narcotics has been exerted by these old-world imports.

“Greasers are taking over the whole operation,” one Federal informant explained. “Carlos Marcello has spread them through the South and the Southwest. They are in upstate New York. Gambino and Marcello and Magaddino are bringing Sicilians over. Right here, in downtown New York, the numbers are all theirs. Joe Mush had a gigantic policy operation, but the greasers told him ‘bow or you’re dead.’ First they started by just hanging around, but pretty soon they were bringing over their buddies, until today, on Mulberry Street, the American wise guys are scared of them.”

“These guys are bringing everybody into line. They’ve got the old man’s okay, and when they move it’s going to be a bloody mess.”

--

On August 4, in Trinchi’s Restaurant in Yonkers, the first of the mob’s meetings took place. Despite the fact that it was held in public on a busy Friday night, it was not until months later that the New York City police found out that it had taken place. (Inexplicably, the NYPD, to the mob’s delight, has decided to cut back the kind of surveillance work needed to fight organized crime.) The FBI had apparently missed the meeting as well, and, if it had not been for an IRS agent in search of an acquaintance of one of those who attended the meeting, no law enforcement unit would have known of the meeting. Those attending included Carmine Tramunti, acting head of the Lucchese family, long known for its drug operations. Based in East Harlem, it had a virtual monopoly in supplying drugs to black and Puerto Rican ghettos before the Mafia-imposed ban. While Tramunti has no personal involvement with narcotics (his interests are almost exclusively gambling), as the family’s titular head his approval was not only expected but required. Philip Rastelli, acting boss of the Bonanno family, was also present. The Bonannos have been well known as a drug family since the early 1930s, when Joseph Bonanno first put the Sicily-Marseilles-Montreal-New York route together. The Bonanno Mafia family has always been evenly divided between Montreal and New York, and it has specialized in smuggling of all kinds. Rastelli, who has taken over the Bonanno mob and moved into a racket vacuum in New Jersey, is expected to be the first Mafia boss to make a move in solidifying the drug business. Bonanno soldiers, perhaps more than those of any other family, have been most debilitated by internal wars, jail, and a loss of illicit income. Bookmaking, loanshark concessions, labor union infiltration, waterfront pilfering franchises—all of the fringe benefits and income that accompany a thriving Mafia family—were denied the Bonanno crew as a result of their leadership vacuum after Joseph Bonanno was kidnapped and his heir was rejected by the Mafia’s commission. As a result, it is the remnants of the old Bonanno family who are most in need of the drug trade, and it will therefore fall to Rastelli in New Jersey to take on the well-organized and deeply entrenched Cuban gangs. He is expected to go about it, according to various police informants, by systematically killing off top Cuban importers until eventually the entire Cuban operation is under control. With Rastelli at all of the meetings was another Bonanno boss, Natale Evola, an older and highly respected don. It is Evola who often serves as a voice of moderation when Rastelli, who has a volatile nature, explodes.

Also present at the meeting was Michael Papa, the 24-year-old nephew of Vincent Papa, the Lucchese family associate arrested last February with the cash-filled green suitcase. It is suspected that Michael, who was on bail at the time of the dinner, was representing his uncle’s interests. The last and most mysterious of the Mafia dinner companions was Francesco Salamone, an illegal Sicilian alien who has a long history of international narcotics smuggling and many Corsican friends.

A second meeting took place on August 11, the day after the two Manfredi nephews were shot and killed, and it was held at the Staten Island home of John (Johnny Dee) D’Alessio, a Carlo Gambino captain. At this meeting, Evola, Rastelli and Salamone, their European connection, apparently presented their plans to the bosses and acting bosses of other Mafia families. Present were acting Genovese boss Alphonse (Funzie) Tieri; septuagenarian, gum-chewing Michele Miranda, a highly respected Genovese family consigliere; Aniello DellaCroce, Carlo Gambino’s most likely successor; Alphonse (Allie Boy) Persico, representing his brother Carmine (Junior) Persico, a Colombo family captain, and Joseph N. Gallo, a man, unrelated to the Brooklyn Gallos, who often represents the interests of the New Orleans and Tampa Mafia families in New York. (Trafficante and Marcello both refused to attend the meetings, according to police, since their last dinner with friends in New York resulted in their seizure in La Stella Restaurant on Queens Boulevard.) Gallo’s presence at the meeting, therefore, was significant since it is through the Far-Easten connections established by the bosses of the two southern Mafia families that so much of the heroin brought into the United States originates. Also attending the second meeting was Luciano Leggio—another illegal Sicilian alien wanted for murder in Palermo and an old-world Mafioso with excellent Corsican connections.

The third meeting, at which Evola and Rastelli once again presided, is expected to be the last. It took place on August 17, in Gargiulo’s Restaurant on West 15thStreet, off Mermaid Avenue, in Coney Island. The acting Genovese boss, Alphonse Tieri, and the Lucchese boss, Carmine Tramunti, were present, as was Joseph N. Gallo. The five men met on a Thursday evening and sat down to dinner unnoticed by the rest of the customers. They were, after all, five neatly dressed, soft-spoken businessmen who were discussing, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, the problems inherent in any new business venture.

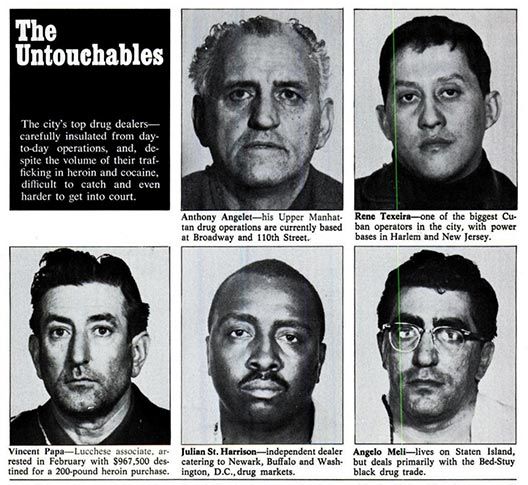

The Untouchables

The city’s top drug dealers—carefully insulated from day-to-day operations, and, despite the volume of their trafficking in heroin and cocaine, difficult to catch and even harder to get into court.

Anthony Angelet—his Upper Manhattan drug operations are currently based at Broadway and 110thStreet.

Rene Texeira—one of the biggest Cuban operators in the city, with power bases in Harlem and New Jersey.

Vincent Papa—Lucchese associate, arrested in February with $967,500 destined for a 200-pound heroin purchase.

Julian St. Harrison—independent dealer catering to Newark, Buffalo and Washington, D.C., drug markets.

Angelo Meli—lives on Staten Island, but deals primarily with the Bed-Stuy black drug trade.

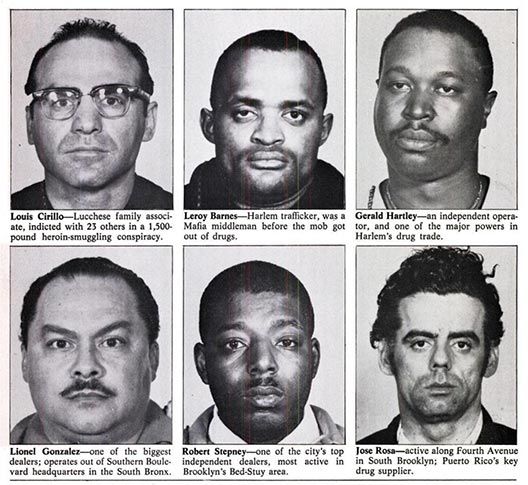

Louis Cirillo—Lucchese family associate, indicted with 23 others in a 1,500-pound heroin-smuggling conspiracy.

Leroy Barnes—Harlem trafficker, was a Mafia middleman before the mob got out of drugs.

Gerald Hartley—an independent operator, and one of the major powers in Harlem’s drug trade.

Lionel Gonzalez—one of the biggest dealers; operates out of the Southern Boulevard headquarters in the South Bronx.

Robert Stepney—one of the city’s top independent dealers, most active in Brooklyn’s Bed Stuy area.

Jose Rosa—active along Fourth Avenue in South Brooklyn; Puerto Rico’s key drug supplier.

*A version of this article appeared in the January 8, 1973 issue of New York Magazine.